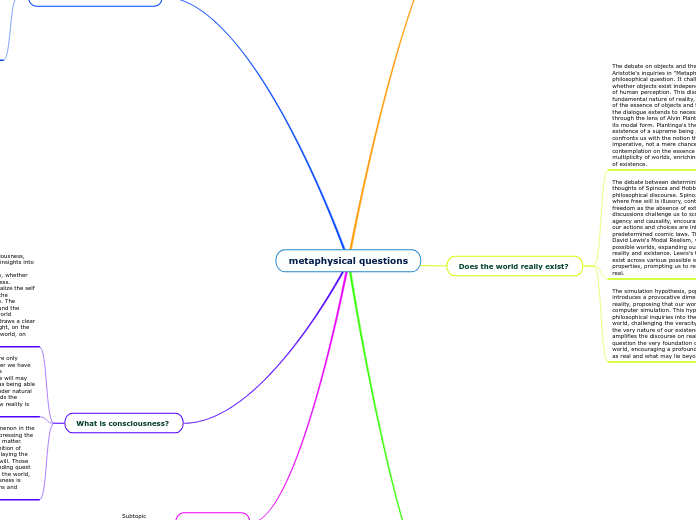

metaphysical questions

What is our place in the universe?

Cosmology and Cosmogony relate to the study of the origin, structure, and ultimate fate of the universe. Cosmology tries to understand the universe at large and does this by the use of theories such as the Big Bang to explain the nature of the universe. Usually, theology deals with the cosmogony because it is one theory of the purpose and creation of the universe from a spiritual or divine point of view. This is the very juncture that invites us to think of human place not only in the physical universe but also of their place in the metaphysical universe.

Space and Time serve as the fundamental fabric of the cosmos, within which all physical phenomena occur. The Principle of Relativity, introduced by Albert Einstein, revolutionizes our understanding of these concepts by describing how measurements of time and space are relative to the velocity of the observer. This principle suggests that our perception of space and time is inherently linked to our position and movement within the universe, implying that our place is not fixed but dynamic and relative.

Necessity and Possibility, central to the Cosmological Argument, examines the existence of the universe from the perspective of modal logic. This line of thinking puts the argument across that the universe must have a first cause or necessary being that explains the universe's existence. This particular framework of necessity versus possibility compels the very many debates over the very basic nature of our universe and our existence in it as contingent beings.

Does the world really exist?

The debate on objects and their properties, tracing back to Aristotle's inquiries in "Metaphysics," continues to be a pivotal philosophical question. It challenges us to contemplate whether objects exist independently or are merely constructs of human perception. This discourse invites us to probe the fundamental nature of reality, urging a deeper understanding of the essence of objects and their attributes. Alongside this, the dialogue extends to necessity and possibility, particularly through the lens of Alvin Plantinga's Cosmological Argument in its modal form. Plantinga's thesis, asserting the essential existence of a supreme being as the universe's underpinning, confronts us with the notion that the universe's existence is an imperative, not a mere chance. This perspective fosters a contemplation on the essence of reality and the conceivable multiplicity of worlds, enriching our philosophical exploration of existence.

The debate between determinism and free will, fueled by the thoughts of Spinoza and Hobbes, remains a cornerstone of philosophical discourse. Spinoza's deterministic universe, where free will is illusory, contrasts with Hobbes's view of freedom as the absence of external constraints. These discussions challenge us to scrutinize the nature of human agency and causality, encouraging a deeper reflection on how our actions and choices are influenced by or independent of predetermined cosmic laws. This debate intertwines with David Lewis's Modal Realism, which posits the reality of all possible worlds, expanding our conventional understanding of reality and existence. Lewis's theory suggests that entities exist across various possible worlds, each with distinct properties, prompting us to reconsider our notions of what is real.

The simulation hypothesis, popularized by Nick Bostrom, introduces a provocative dimension to our understanding of reality, proposing that our world might be an advanced computer simulation. This hypothesis aligns with age-old philosophical inquiries into the authenticity of our perceived world, challenging the veracity of our sensory experiences and the very nature of our existence. Such a hypothesis not only amplifies the discourse on reality but also invites us to question the very foundation of our understanding of the world, encouraging a profound reevaluation of what we accept as real and what may lie beyond our conventional perceptions.

Why is there something, rather than nothing?

The exploration of objects and their properties, as discussed by philosophers like Locke and Aristotle, delves into the nature and essence of objects and their inherent characteristics, whether they are perceptible or not. This line of inquiry prompts a deeper examination of existence, proposing that objects and their interactions are fundamental to the fabric of reality. Causality and contingency further expand this philosophical landscape. Causality connects cause and effect, deeply ingrained in our understanding of the universe, while contingency suggests the potential for things to be different, highlighting the non-necessity of the universe's existence and prompting reflections on why anything exists at all.

Existential ontology, a field probed by philosophers like Heidegger, questions the very nature of being and the reason for existence as opposed to nothingness. Heidegger posits that questioning our existence unveils the profound nature of being, pushing us to consider the essence of existence beyond physical properties. Various theories, such as the Anthropic Principle and quantum mechanics, offer perspectives on this existential inquiry. The Anthropic Principle suggests a necessary compatibility between the universe and conscious beings, while quantum mechanics introduces the idea of quantum fluctuations, where the emergence of 'something' from 'nothing' is seen as a natural possibility.

In practical terms, these philosophical discussions intersect with modern scientific and theological debates. Cosmology and physics explore the universe's origins, shedding light on how existence could stem from non-existence. Theologically, the discussion often revolves around the concept of a creator or prime mover, offering a foundational cause or rationale for the existence of everything. This intertwining of philosophical thought, scientific exploration, and theological inquiry forms a comprehensive framework for addressing some of the most profound questions about our reality and existence.

What is the meaning of life?

Existentialism projects that existence precedes essence—man first exists and then shapes and defines himself through his actions; he decides what he wants to become. This type of philosophy emphasizes individual choice and the responsibility that one can carry through their actions. Jean-Paul Sartre, a major proponent in the league of existentialist philosophers, believed that it was individual choices and actions of its people that brought the meaning into life.

Albert Camus gives the philosophy of the absurd, characteristic of dealing with the meaningless life created by an unconcerning universe. However, instead of falling into hopelessness, Camus opines that one can find meaning by embracing the absurdity of existence, which is exemplified by the myth of Sisyphus. In this story, Sisyphus finds a way of rebellion and hence meaning in his endless pursuit of the futile task.

Religious existentialism introduces a spiritual dimension to the quest for meaning. Søren Kierkegaard, a forerunner of this perspective, emphasized faith as a critical element in navigating the absurdities of life and finding purpose. According to Kierkegaard, meaningfulness stems from a "leap of faith," a profound and often paradoxical embrace of beliefs that transcend rational explanation.

What is consciousness?

the intricate relation between existence and consciousness, and the mind and matter debates, gives profound insights into the reality and human experience. Existence and Consciousness plunge into the core of metaphysics, whether the nature of being is so or the essence of awareness. Consciousness is more than being aware; it can realize the self and distinguish between the existence of self and the relatedness of existence with conscious experience. The debate on Mind and Matter therefore revolves around the nature of consciousness (mind) and the physical world (matter). Dualistic Theory, in the Descartian line, draws a clear line: the mind, a realm of consciousness and thought, on the one hand, and the physical body and the material world, on the other hand.

Determinism and Free Will, discuss whether we are only allowed to be predestined for our actions or whether we have the freedom to choose. Spinoza sees everything as determined by the laws of nature, perhaps our free will may be just an illusion, whereas Hobbes sees free will as being able to act at liberty according to his desires but still under natural laws. Ontology digs deep into the essence that holds the existent and conscious itself as a basic point of how reality is and the place it holds.

Philosophical questions of this sort find the phenomenon in the real world. It is a true, yet not real experience, expressing the dualistic relations of interaction between mind and matter. From everyday choices up to determining the definition of reality, consciousness somehow affects these, displaying the incessant dialectic between determinism and free will. Those ideas and theories speak together for the never-ending quest to understand the very essentials of our being and the world, leading to questions on how strongly our consciousness is understood, the essence of being, and the freedoms and limitations of reality that shape our own selves.

references :)

References

Aristotle. (n.d.). Categories.

Aristotle. (n.d.). Metaphysics.

Barth, K. (1932). The Doctrine of the Word of God.

Bostrom, N. (2003). Are You Living in a Computer Simulation? Philosophical Quarterly, 53(211), 243–255.

Carter, B. (1974). Large number coincidences and the anthropic principle in cosmology. In Confrontation of Cosmological Theories with Observational Data (pp. 291–298). Springer, Dordrecht.

Craig, W. L. (1979). The Kalam Cosmological Argument. Harper & Row.

Einstein, A. (1915). Relativity: The Special and General Theory.

Hawking, S. (1988). A Brief History of Time. Bantam Dell Publishing Group.

Heidegger, M. (1927). Being and Time.

Hendricks, S. (n.d.). 4 philosophical answers to the meaning of life. Big Think. Retrieved from https://bigthink.com/thinking/four-philosophical-answers-meaning-of-life/

Hobbes, T. (1651). Leviathan.

Hume, D. (1748). An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding.

Krauss, L. M. (2012). A Universe from Nothing: Why There Is Something Rather than Nothing. Free Press.

Leeming, D. A. (2010). Creation Myths of the World. ABC-CLIO.

Lewis, D. (1986). On the Plurality of Worlds. Blackwell.

Locke, J. (1689). An Essay Concerning Human Understanding.

Plantinga, A. (1974). The Nature of Necessity. Clarendon Press.

Poincaré, H. (1902). Science and Hypothesis.

Spinoza, B. (1677). Ethics.

Aquinas, T. (n.d.). Summa Theologica.