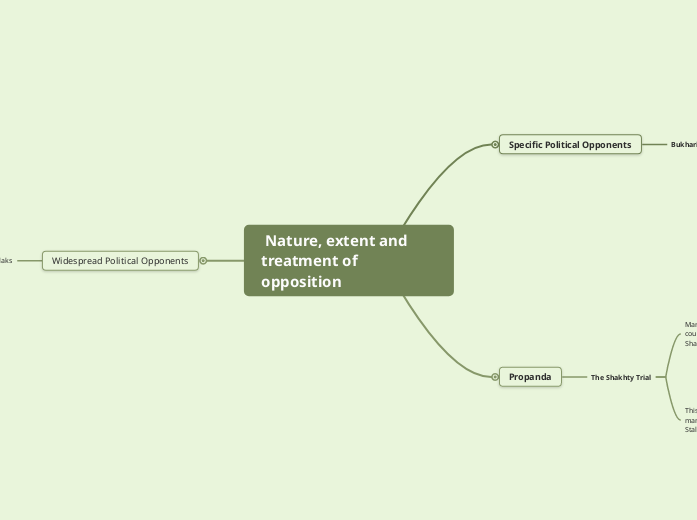

Nature, extent and treatment of opposition

Specific Political Opponents

Bukharin

Bukharin, however, was not in favour of Stalin’s policy. Ostensibly, Bukharin was in a secure position, as many communist party luminaries supported the NEP. He was also the editor of Pravda, which allowed him to affirm to the public that the NEP had not been abandoned - Stalin did not dare contradict him, not wanting to be seen as breaking from Leninism.

Both Stalin and Bukharin were in vulnerable positions. Bukharin, having just destroyed the United Opposition, did not want the party to present a broken front, and Stalin knew that he could not yet exercise complete authority over the Politburo

As a result of Bukharin’s attempts to defend the NEP, the increase in prices offered by the state for agricultural produce failed to induce the peasantry to return to the market on the desired scale.

Bukharin was sacked from the Politburo in November 1929.

Propanda

The Shakhty Trial

March 1928 : Central Committee’s announced a counter-revolutionary plot among engineers at the Shakhty coal mines (made up opposition (probably)

Managers and economists were pressured to meet unrealistic production targets set by the Gosplan (the State Planning Committee), knowing that failure to comply could result in dismissal, imprisonment, or even execution.

The engineers were physically abused by the OGPU

Forced to memorise self-incriminations and paraded in a show trail in May and June 1928. This ended with 5 of the miners being executed and many others being given long sentences.

Stalin took close interest in the decisions made about the engineers.

This trial was used to intimidate economists, managers, and party officials that objected to Stalin's policies and methods of industrial growth.

Widespread Political Opponents

Kulaks

Precursors to persecution

It was laid down that collective farms should be formed exclusively from poor and middling peasant households. "Kulaks" were divided into three categories.

1) those from households most hostile to the government were to be dispatched to forced-labour settlements or shot

2) kulaks belonging to households less hostile to the government were to be sent to distant provinces,

3) those belonging to the least ‘dangerous’ households were to be allowed to stay in their native district, but on a smaller patch of land.

Between 5-7 million people were treated as belonging to kulak families.

Persecution (Dekulakization)

This decree could not be executed with the Red Army and OGPU - their numbers were insufficient, and the Politburo could not depend on the implicit obedience of officers of rural origins.

25,000-ers

Approximetely 25,000 young thugs from factories, the militia, and the party went out to the villages to enforce the establishment of collective farms. The ‘25,000-ers’ were told that the kulaks were responsible for organising a ‘grain strike’ against the town.

They were not issued with instructions of how to distinguish the poor, middling, and rich peasants from each other, nor given any limits on use of violence.

When the ‘25,000-ers’ arrived in the villages, they saw that many hostile peasants were far from being rich. As a result the central party apparatus invented the ‘sub-kulaks’ - those not not rich enough to be kulaks but who opposed the government. Stalin’s persecution was not restricted to better off households.

The Results of Dekulakization

The result of collectivization was the death of 4-5 million people in 1932-3 from ‘dekulakization’ and grain seizures.

The dead and dying were piled onto carts by the urban detachments and pitched into common graves - pits were dug outside the villages for that purpose.

Child survivors ate grass and tree-bark and begged for crusts.

While the government’s policies were killing peasants, peasants were killing and eating their livestock rather than letting them be expropriated by collective farms.

Some officials were horrified at the effects, but did not criticise mass compulsory collectivisation as general policy.