Last updated:

1 September 2025

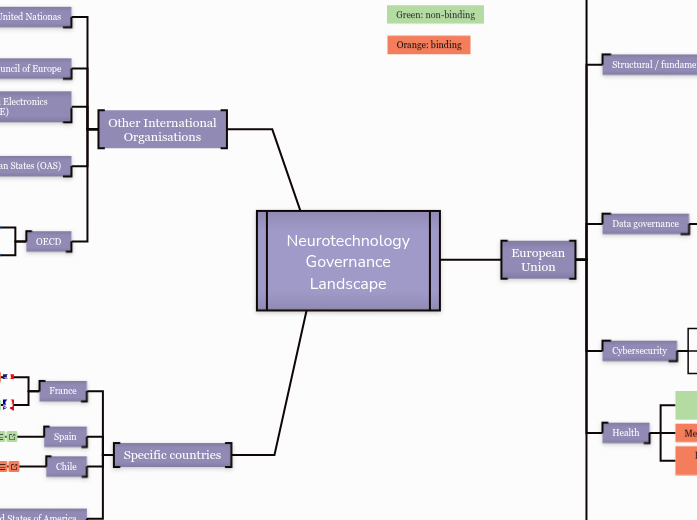

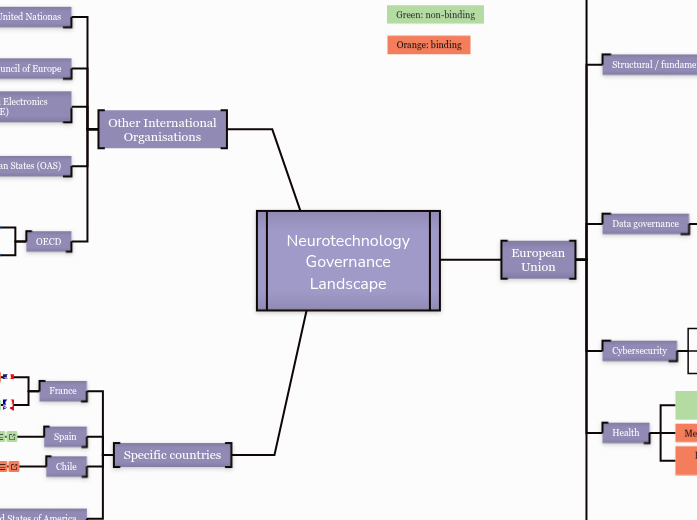

Legend

Green: non-binding

Orange: binding

Neurotechnology Governance Landscape

Specific countries

United States of America

California Consumer Privacy Act - 2024

Introduction

The California Consumer Privacy Act (2024), passed unanimously, amends California's existing data privacy laws to include neural data as "sensitive personal information."

California residents can now request, delete, correct and limit what data a neurotech company collects on them. They can also opt out from companies selling or sharing their data. This law has prompted certain neurotechnology companies (e.g. Emotiv) to introduce specific articles for California residents in their privacy policies.

Selected Relevant Articles

- Article ae(G(ii)): Defines "sensitive personal information" as information that reveals a consumer’s neural data, meaning information that is generated by measuring the activity of a consumer’s central or peripheral nervous system, and that is not inferred from nonneural information.

Conclusions and Analysis

- The bill faced pushback from Big Tech companies, who argued that including the peripheral nervous system would “sweep too broadly and ensnare nearly any technology that records anything about human behavior.” (Moens, 2024).

- Because California is home to Silicon Valley—with many neurotechnology startups and major tech companies (including Apple) expanding into neurotech—this bill holds particular significance in the broader tech policy landscape.

Sources and Further Reading

Colorado Privacy Act - 2024

Introduction

In 2024, Colorado became the first U.S. state to pass a bill to explicitly extend privacy rights to neural data, known as the "Colorado Privacy Act." It mandates that companies must treat neural data as sensitive information, and secure consent before collecting or processing it.

Selected Relevant Articles

- Section 1(d): Recognises neural data as extremely sensitive, and potentially revealing intimate information about individuals, including information about health, mental states, emotions, and cognitive functioning;

- Section 1(e): Designates that all neural data is by definition sensitive and identifiable to the individual, as it always contains distinctive information about the structure and functioning of individual brains and nervous systems.

Conclusions and Analysis

- The Colorado Privacy Act is part of a trend of growing importance given to the protection of neural data spreading across the Americas.

- Significantly, the language it contains designating all brain data as identifiable to the individual sets an important precedent for how neural data might be classified in other jurisdictions, namely by the GDPR.

Sources and Further Reading

Chile

"Neurorights" amendment to the Chilean constitution - 2021

Introduction

In 2021, Chile became the world’s first country to explicitly enshrine neurorights into its legal framework. The Chilean Senate approved a constitutional amendment adding explicit protections to mental integrity and brain data.

In 2023, Chile’s Supreme Court became the first court to rule on a neuroprivacy case. Chile’s Supreme Court ruled that Emotiv's “Insight” device violated Senator Girardi’s constitutional rights by collecting and retaining his brain data data for research purposes, even in anonymised form, without explicit consent. This landmark neuroprivacy decision establishes a significant legal precedent and underscores the growing influence of the neurorights movement (Do, 2024).

Relevant Article

- The Chilean constitutional amendment added a new section to the Chilean Constitution Article 19, stating: "Scientific and technological development will be at the service of people and will be carried out with respect for life and physical and mental integrity. The law will regulate the requirements, conditions and restrictions for its use by people, and must especially protect brain activity, as well as the information from it."

Conclusions and Analysis

- Chile’s experience sets a powerful global precedent for enshrining neuroethics principles into law.

- It also acted as a catalyst – after Chile, other countries (e.g. Spain, Mexico, Brazil, certain U.S. states) have since followed with similar proposals.

- Aside from the Chilean Supreme Court ruling, legal implementation of this new constitutional amendment is unclear. For instance, it remains unclear whether neurodata should be categorised as personal data for legal purposes. (Cornejo-Plaza, 2024).

Sources

- Do, B., Badillo, M., Cantz, R., Spivack, J., Privacy and the Rise of “Neurorights” in Latin America. Future of Privacy Forum, 2024.

- TechDispatch #1/2024 - Neurodata, European Data Protection Supervisor, 2024.

- Guzmán, L., Chile: Pioneering the protection of neurorights. UNESCO Courier, 2022.

- Cornejo-Plaza M., Cippitani, R., Pasquino, V., Chilean Supreme Court ruling on the protection of brain activity: neurorights, personal data protection, and neurodata. Front. Psychol. 2024.

Spain

Spanish Charter of Digital Rights - 2018

Introduction

The Spanish Charter of Digital Rights, adopted in 2018, provides a non-binding framework to guide public authorities in addressing digital rights, including neurotechnologies. Developed by the Expert Advisory Group under Spain’s State Secretariat for Digitalization and Artificial Intelligence, it reflects Spain’s commitment to ethical and inclusive digital governance. While not legally enforceable, the Charter establishes critical principles on the use of neurotechnologies, particularly in safeguarding personal identity, ensuring self-determination, and protecting brain-related data.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- Neurotechnologies must ensure that individuals retain control over their identity, preventing alterations or exploitation through neural implants or brain-machine interfaces.

- Emphasiszes autonomy, sovereignty, and freedom in decision-making, especially regarding the use or implantation of neurotechnological devices.

- Strong safeguards must be in place to ensure the confidentiality, security, and user control of brain-derived data and processes.

- The Charter advocates for laws to regulate neurotechnologies to ensure ethical use, free from bias, incomplete information, or coercion that may affect mental or physical integrity.

- Calls for laws to govern non-therapeutic neurotechnologies, including those aimed at cognitive or mental augmentation, ensuring they align with dignity, equality, and non-discrimination.

- Serves as a reference for public authorities to regulate neurotechnologies in alignment with human dignity and rights, fostering responsible innovation and ethical governance.

Selected Relevant Articles

- XXI: Research in neuroscience, genomics, and bionics must respect human dignity, self-determination, privacy, and integrity, in line with ethical standards.

- XXVI: Digital rights in neurotechnology use prioritisze individual control over identity, autonomy in decision-making, and security of brain data. This includes specific safeguards for human-machine interfaces and the prevention of coercion, bias, or manipulation in neurotechnological applications.

Conclusions and Analysis

- By emphasising dignity, autonomy, and security, the Charter positions Spain as a leader in promoting ethical principles for neurotechnological development.

- Its focus on identity, self-determination, and non-discrimination ensures neurotechnologies align with human values and rights.

- The inclusion of non-therapeutic applications highlights a forward-looking approach, addressing emerging neurotechnological innovations like cognitive augmentation.

- Though non-binding, the Charter’s principles could inspire legally enforceable regulations in Spain and contribute to broader EU-level governance frameworks.

Sources

France

French charter for the responsible development of neurotechnologies - 2022

Introduction

The French Charter for the Responsible Development of Neurotechnologies (2022) provides a comprehensive, non-binding framework to guide the ethical, inclusive, and secure development of neurotechnologies in France, aligned with the OECD Recommendation on Responsible Innovation in Neurotechnologies. The Charter addresses critical issues such as brain data protection, device safety, and ethical communication, responding to societal concerns and potential risks associated with neurotechnologies.

Principles

- Principle 1: Protects brain data through transparency, rigorous consent processes, and secure data management, acknowledging its unique sensitivity and potential for misuse.

- Principle 2: Ensures reliability, safety and efficacy of devices (medical and non-medical) through protection from intrusion, demonstrated effectiveness (not necessarily clinical trials), reversibility, and user feedback.

- Principle 3: Advocates for ethics-driven innovation, particularly by mitigating hype (good and bad) and ensuring transparency of efficacy and use of AI.

- Principle 4: Prevents misuse and malicious uses, such as manipulative, unconsented surveillance, or coercive applications, opposing uses that limit freedom and self-determiniation.

- Principle 5: Recognises the need to address societal expectations by fostering reflectivity, inclusivity, dialogue, equity of access and vigilance throughout the design phase.

Conclusions and Analysis

- While not legally enforceable, the Charter establishes a first precedent for the specific protection, ethical use, and transparency of brain data on an EU Member State level, and provides an influential framework for shaping national and international policies. For example, this Charter inspired the European Charter for Responsible Development of Neurotechnologies.

- The emphasis on preventing unethical applications builds public trust and ensures neurotechnologies serve societal good.

- Positions France as a leader in neuroethics.

Sources

The French Bioethics Laws - 2011 and 2021

Introduction

The French Bioethics Laws (2011 and 2021) form a comprehensive legal framework addressing bioethical challenges in France, with a focus on genetics, neuroscience, and innovative medical technologies. The 2021 amendments build on the 2011 law, updating regulations to address the privacy, ethical considerations, and potential misuse of brain data.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- Brain imaging technologies are strictly regulated to ensure their use aligns with human dignity and mental integrity, requiring express, informed, and revocable consent.

- Brain imaging techniques may only be used for medical, scientific, or judicial purposes, with functional brain imaging explicitly excluded from judicial expertise under the 2021 amendments.

- Acts or technologies that modify brain activity and pose a serious danger to human health may be banned through decree, following consultation with the High Authority for Health.

- Regular reports on advancements in neuroscience must be shared with Parliament, ensuring public oversight and ethical governance of emerging neurotechnologies.

- Brain imaging data is explicitly included in criminal code protections, recogniszing its sensitivity and ensuring ethical handling.

Selected Relevant Articles

2011 Law:

- Article 45: Requires express, informed, and revocable consent for brain imaging used in medical, research, or judicial contexts.

- Article 48: Mandates ethical review of neuroscience practices.

2021 Law:

- Article 18: Bans functional brain imaging other than in medical and research contexts, and extends data protection rules to brain imaging techniques.

- Article 19: Prohibits brain-modifying technologies deemed dangerous.

- Article 39: Requires continuous reporting to Parliament and Government on advancements in neuroscience.

Conclusions and Analysis

- The explicit regulation of brain imaging and brain data privacy in the 2021 revision reflects France's proactive approach to neuroethics.

- Neurotech companies operating in France must adhere to these standards, especially concerning the collection, processing, and use of brain data.

- The periodic review requirement ensures that bioethical laws remain relevant amidst advancing technologies, providing a robust legal framework for neurotechnology.

Sources

Other International

Organisations

OECD

OECD Neurotechnology Toolkit - 2024

Introduction

The OECD Neurotechnology Toolkit, released in April 2024, serves as a central resource for policymakers to support the implementation of neurotechnology-related policies, emphasising practical guidance across multiple principles and jurisdictions. It illustrates the 5 building blocks of the OECD Framework for Anticipatory Governance of Emerging Technologies with examples of implementation for neurotechnology governance from Member States.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- Assists policymakers in effectively governing neurotechnologies using examples from the five building blocks of the OECD Framework for Anticipatory Governance:

- Guiding Values

- Strategic Intelligence

- Stakeholder Engagement

- Agile Regulation

- International Cooperation

- Provides tools and strategies to anticipate, prepare for, and address challenges associated with emerging neurotechnologies.

- By suggesting possible actions for implementing each building block and principle of the OECD, it helps build governance capacities towards neurotechnology regulation and policy.

- Encourages partnerships between governments, innovators, and societies across all stages of the innovation process.

Conclusions and Analysis

- Though not legally-binding, this toolkit serves as a key advisory framework for policy-makers, fostering flexibility and deliberation while encouraging widespread adoption and implementation.

- Represents a continuation of the OECD's leadership in neurotechnology governance, complementing the 2019 Recommendation.

Sources

OECD Recommendation on Responsible Innovation in Neurotechnology - 2019

Introduction

The OECD Recommendation on Responsible Innovation in Neurotechnology (2019) is the first international standard in this domain. While legally non-binding, it provides a robust framework for promoting responsible innovation in neurotechnology, focusing on safety, inclusivity, scientific collaboration, and societal deliberation. It embodies 9 core principles for the responsible development of neurotechnology:

- Promoting responsible innovation

- Prioritising safety assessment

- Promoting inclusivity

- Fostering scientific collaboration

- Enabling societal deliberation

- Enabling capacity of oversight and advisory bodies

- Safeguarding personal brain data and other information

- Promoting cultures of stewardship and trust across the public and private sector

- Anticipating and monitoring potential unintended use and/or misuse

Since its adoption, 39 countries have adhered to this recommendation.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- Encourages responsible neurotechnology development to address health challenges while conducting rigorous safety assessments and mitigating risks, including misuse.

- Supports interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral collaboration while strengthening oversight and advisory bodies to tackle complex challenges.

- Emphasises safeguarding brain data and other sensitive information, aligning with ethical and legal standards.

- Encourages public dialogue to align neurotechnologies with societal values and foster trust through ethical practices in both public and private sectors.

Conclusions and Analysis

- This recommendation provides a comprehensive framework for responsible neurotechnology innovation, emphasizing the balance between innovation and addressing ethical, societal, and safety concerns.

- Its wide adoption suggests strong international support for these principles.

- However, as a non-binding instrument, its enforceability relies on the commitment of member states.

Source

Organization of American States (OAS)

Inter-American Declaration of Principles on Neuroscience, Neurotechnologies and Human Rights - 2023

Introduction

The Inter-American Declaration of Principles on Neuroscience, Neurotechnologies, and Human Rights (2023) by the Inter-American Juridical Committee of the Organisation of American States (OAS), is a non-binding instrument that provides guidance on the ethical and human rights implications of neuroscience and neurotechnologies.

It applies across the 35 member states of the OAS, including countries in North, Central, and South America and the Caribbean. The declaration builds on principles from the Inter-American Human Rights System and serves as a key reference point for addressing emerging challenges posed by neurotechnologies in the Americas.

Principles

- Principle 1: Protects identity, autonomy, and privacy of neural activity, acknowledging that Neural activity generates the totality of the mental and cognitive activities of human beings, and therefore forms part of the essence of a person’s very being.

- Principle 2: Promotes a human-rights-by-design approach to neurotechnology development.

- Principle 3: Recognises neural data as highly sensitive personal data. Its collection and use must respect individual privacy and cognitive autonomy, ensuring informed consent and robust safeguards against misuse.

- Principle 4: Mandates free, informed, express, specific, unequivocal, and flawless consent as a prerequisite for access to the collection of brain information.

- Principle 5: Promotes equality, non-discrimination, and equal access to neurotechnologies.

- Principle 6: Calls for caution and limits around cognitive enhancement not linked to medicine and therapy.

- Principle 7: Protects neurocognitive integrity, specifying that neurotechnologies must not infringe on freedom of thought and conscience. Bans compulsive or forced application, as well as use for torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.

- Principle 8: Calls for transparency of governance by all actors (state or non-state) involved in the development and/or marketing of neurotechnologies.

- Principle 9: Calls on States to establish national authorities to monitor the development and application of neurotechnologies, ensuring they are aligned with international human rights standards.

- Principle 10: States that individuals should have access to effective protections and legal remedies for any human rights violations arising from neurotechnologies.

Conclusions and Analysis

- The Inter-American Declaration provides a forward-looking ethical framework for addressing the unique challenges posed by neurotechnologies. While not legally binding, it offers guidance to member states on integrating human rights considerations into neurotechnology research, development, and deployment.

- Key principles such as privacy-by-design, informed (and flawless!) consent, limiting non-therapeutic cognitive enhancement, and the establishment of national authorities are particularly significant in promoting a precautionary approach in an era of rapid technological advancement.

- The declaration further emphasises the importance of transparent governance and accessible remedies for any harm caused, ensuring accountability and fairness across all stages of neurotechnology implementation.

Sources

American Convention on Human Rights - 1969

Introduction

The American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR), adopted in 1969 under the Organization of American States (OAS), is a legally binding treaty aimed at protecting human rights and fundamental freedoms across the Americas. It applies to the OAS member states that have ratified it, including countries in North, Central, and South America and the Caribbean. The ACHR is a cornerstone for human rights protection in the region and influences national laws and policies in various fields, including the emerging area of neurotechnology.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- Neurotechnologies must respect the right to privacy. States may only interfere with this right under specific, justified circumstances, such as protecting public safety or health.

- Neurotechnologies should safeguard freedom of thought and expression, avoiding undue influence on cognitive functions or misleading claims about capabilities.

- Neurotechnologies must be accessible to all, ensuring benefits are equitably distributed regardless of gender, disability, or other factors.

- The ACHR, supported by the Inter-American Commission and Court of Human Rights, ensures accountability for human rights violations.

- Neurotechnologies must balance innovation with the protection of individual freedoms, allowing limitations only when justified for public safety or health concerns.

Selected Relevant Articles

- Article 11: Right to Privacy protects individuals from arbitrary interference with their private life.

- Article 13: Right to Freedom of Though and Expression guarantees cognitive freedom, ensuring individuals are free from undue external influence on their thought processes.

- Article 25: Right to Judicial Protection provides access to remedies for rights violations related to neurotechnologies.

- Article 26: Encourages the responsible development of technologies to advance societal benefits while respecting fundamental rights.

Conclusions and Analysis

- The ACHR serves as a foundational human rights instrument, providing guidance for the ethical use and regulation of neurotechnologies in the Americas.

- Provisions on privacy and freedom of thought are particularly significant for neurotechnologies that interact with cognitive functions or process sensitive neural data.

- Additionally, the oversight provided by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and Inter-American Court of Human Rights offers clarity and consistency in interpreting and applying these rights to emerging technologies.

Sources

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE)

IEEE SA Standards Roadmap: Neurotechnologies for Brain-Machine Interfacing - 2020

Introduction

The IEEE SA Standards Roadmap: Neurotechnologies for Brain-Machine Interfacing (2020), provides a detailed framework for guiding developments in neurotechnologies related to brain-machine interfacing. While not legally binding and not a formal IEEE standard, the roadmap serves as a strategic document addressing public perception, sensor technologies, end-effectors, data management, and user needs in the neurotechnology space.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- Focuses on key aspects such as public perception, sensor technology, end-effectors, data presentation, and performance benchmarking.

- Covers both invasive and non-invasive neurotechnologies, including novel minimally-invasive approaches like the Stentrode system.

- Serves as a roadmap rather than a consensus-based standard, offering strategic guidance rather than enforceable norms.

- Provides a foundation for future standards development in brain-machine interfacing.

Conclusions and Analysis

- The roadmap provides a forward-looking framework for addressing technological, societal, and performance challenges in brain-machine interfacing.

- It highlights the need for integrating user needs and public perception into the design and implementation of neurotechnologies.

- Its advisory nature allows flexibility but does not provide enforceable standards.

- It establishes a basis for future IEEE consensus standards in the neurotechnology domain.

Sources

Council of Europe

European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) - 1950

Introduction

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), signed in 1950 under the Council of Europe, is a legally binding treaty aimed at protecting human rights and fundamental freedoms in Europe. It applies to all 46 Council of Europe countries, including 27 EU member states, and serves as a cornerstone for European human rights law. The ECHR's principles underpin many EU regulations and national laws, influencing policies across various fields, including neurotechnology.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- Neurotechnologies must respect private life and ensure careful handling of personal and potentially invasive data. States may only interfere with this right under specific, justified circumstances (e.g., public safety, prevention of crime, or health protection).

- Neurotechnologies should protect freedom of thought and expression, avoiding undue influence on cognitive functions or misleading claims.

- Neurotechnologies must be inclusive, ensuring equitable access and benefits for all users regardless of gender, disability, or other status.

- Legal clarity on human rights in neurotechnologies is supported by the European Court of Human Rights and advisory opinions.

- Neurotechnologies must balance innovation with individual freedoms, allowing limitations only for justified public safety or health concerns.

Selected Relevant Articles

- Article 8: Right to respect for private and family life, with limited exceptions (national security, prevention of crime, health, or protection of rights of others.)

- Article 9: Guarantees freedom of thought, conscience, and religion.

- Article 10: Ensures freedom of expression, subject to necessary limitations for public safety or health.

- Article 14: Prohibits discriminationin the enjoyment of ECHR rights.

- Article 47 and Protocol 16: Allows for advisory opinions on ECHR interpretations.

Conclusions and Analysis

- The ECHR serves as a foundational human rights instrument across Europe, guiding the ethical use and regulation of neurotechnologies.

- While the ECHR does not explicitly mention neurotechnology, key rights—such as Article 8 (right to privacy) and Article 9 (freedom of thought, conscience and religion)—are increasingly cited in legal and academic debates as foundational to protecting mental privacy and cognitive liberty in the age of neurotech.

- The "neurorights" movement has prompted widespread debate on whether the ECHR (and other foundational human rights documents) needs to be reinterpreted or expanded to include specific rights for the brain, addressing potential intrusions into thought, identity, and mental integrity posed by neurotechnologies.

- While most experts now agree that the ECHR provides sufficient protections to mental integrity and does not need amending, scholarly attention is now turning to how these human rights principles can be concretely implemented and safeguarded in sector-specific regulation.

Sources and further reading

- European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)

- Report on Neurotechnologies, Human Rights and Biomedicine (Council of Europe).

- Ienca M. On Neurorights. Front Hum Neurosci. Sep 2021.

- Hertz N. Neurorights – Do we Need New Human Rights? A Reconsideration of the Right to Freedom of Thought. Neuroethics. Sep 2022.

- Brown CML. Neurorights, Mental Privacy, and Mind Reading. Neuroethics. Jul 2024.

- Barnard G, Berger L, Dolezal E, Gremsl T, Jarke J, Maia de Oliveira Wood G, Staudegger E, Zandonella P, The protection of mental privacy in the area of neuroscience - Societal, legal and ethical challenges, STOA Study, European Parliamentary Research Service, 2024.

- Istace T. Establishing Neurorights: New Rights versus Derived Rights. J Hum Rights Pract. Feb 2025.

United Nationas

UNESCO

UNESCO Recommendation on the Ethics of Neurotechnology - [expected 2025]

Introduction

The UNESCO Recommendation on the Ethics of Neurotechnology will provide a universal framework for guiding ethical governance in neurotechnology. While legally non-binding, the Recommendation aims to harmonise national legislation and policies with suggested values, principles, rights, and areas of policy action. This Recommendation will assist UN Member States in developing national legislation and policies aligned with international standards.

The first draft was released on June 9, 2024 and submitted to a public consultation. It is currently in inter-governmental negotiations, and the final Recommendation is due for adoption in late 2025.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- Provides definitions of 'neurotechnology', 'neural data', and ‘cognitive biometric data’.

- Offers a universal framework of interpretation of values, principles and human rights to guide global ethical neurotechnology governance.

- Outlines key policy areas where action is needed, including health, education, labor, and vulnerable groups such as youth, women, and individuals with mental health disabilities.

- Specifically highlights the commercial and consumer domains as well as enhancement purposes, with recommendations for governance by Member States.

Conclusions and Analysis

- This Recommendation will be a significant milestone in advancing the global consensus on neurotechnology ethics.

- Its advisory and non-binding nature will promote flexibility, allowing Member States to adapt the recommendations to their specific legal and cultural contexts, while setting fairly strict standards for ethical innovation and applications of neurotechnologies.

Sources and further reading

Universal Declaration of Human Rights - 1948

Introduction

Adopted in 1948 by the United Nations General Assembly, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is a foundational document establishing a common standard of fundamental rights and freedoms for all people. While not legally binding, it has profoundly influenced national constitutions, international treaties, and soft law frameworks—including many human rights instruments relevant to neurotechnology. The UDHR's emphasis on dignity, autonomy, privacy, and non-discrimination makes it an enduring point of reference in global debates about emerging technologies, including those that interact directly with the brain.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- Neurotechnologies must respect the inherent dignity of individuals.

- The UDHR’s protections of privacy and freedom of thought reinforce calls for strong safeguards around neurodata use.

- The UDHR underpins broader international human rights dialogues, including those exploring whether neurorights are best understood as new rights or extensions of existing ones.

Selected Relevant Articles

- Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.

- Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty, and security of person.

- Article 5: No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

- Article 12: No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with privacy or attacks on honour and reputation.

- Article 18: Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion.

- Article 19: Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression.

- Article 27: Everyone has the right to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.

Conclusions and Analysis

- The UDHR remains a global ethical and normative anchor for evaluating the impacts of neurotechnology.

- Although drafted long before such technologies were mainstream, its protections for privacy, dignity, freedom of thought, and equality are frequently invoked in neurorights debates.

- Legal scholars and ethicists largely agree that the UDHR provides a sufficient normative basis for governing neurotechnology, but that operationalising these rights—especially around mental privacy, identity, and cognitive liberty—requires further legal interpretation and policy innovation.

- As neurotechnology advances, the UDHR will likely continue to serve as a touchstone for both national regulations and international soft law efforts aimed at aligning innovation with human rights.

Sources

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)

- Ienca M. On Neurorights. Front Hum Neurosci. Sep 2021.

- Hertz N. Neurorights – Do we Need New Human Rights? A Reconsideration of the Right to Freedom of Thought. Neuroethics. Sep 2022.

- Brown CML. Neurorights, Mental Privacy, and Mind Reading. Neuroethics. Jul 2024.

- Bublitz JC. What an International Declaration on Neurotechnologies and Human Rights Could Look Like: Ideas, Suggestions, Desiderata. AJOB Neurosci. 2024

- Barnard G, Berger L, Dolezal E, Gremsl T, Jarke J, Maia de Oliveira Wood G, Staudegger E, Zandonella P, The protection of mental privacy in the area of neuroscience - Societal, legal and ethical challenges, STOA Study, European Parliamentary Research Service, 2024.

- Istace T. Establishing Neurorights: New Rights versus Derived Rights. J Hum Rights Pract. Feb 2025.

European

Union

Consumer protection

Product Liability Directive - 2024

Introduction

The revised Product Liability Directive (2024) updates the EU framework on liability for defective products. Its aim is to harmonise liability rules across Member States, ensuring consumer protection while maintaining fair competition and the smooth functioning of the internal market.

For neurotechnology, the Directive is highly relevant: it establishes who is liable when neurotech products cause harm (manufacturers, importers, component suppliers, or modifiers) and broadens definitions of both “defective products” and “damage” (including psychological health). Importantly, it also extends liability to digital services integrated into a product, which is particularly relevant for connected or AI-driven neurotech.

The Directive applies to products placed on the market after 9 December 2026.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- Manufacturers, component makers, importers, and even those modifying neurotech devices can be held liable.

- Integrated services (e.g. apps analysing brain data or AI-driven monitoring features) are treated as product components, making companies liable for harm caused by software as well as hardware.

- Medically-certified psychological damage is explicitly compensable—crucial for neurotech where mental health outcomes are at stake.

- Courts may presume defectiveness or causality where scientific/technical complexity makes it excessively difficult for claimants to prove. This is particularly relevant for AI-based or complex brain–computer interface systems.

- Member States and the Commission must publish high-level judgments in product liability cases, creating a public record that could shape precedent for neurotech.

Selected Relevant Articles

- Article 2: Applies to all products placed on the market after December 2026 (excluding free/open-source software developed outside commercial activity).

- Article 5: Any natural person harmed by a defective product has the right to compensation.

- Article 6: Damage includes death, personal injury, and medically certified psychological harm.

- Article 7: A product is defective if it does not provide the safety the public is entitled to expect (based on intended use, foreseeable misuse, risk level, and user group).

- Article 8: Liability extends to manufacturers, component makers, importers, authorised representatives, fulfilment providers, and those who substantially modify products.

- Article 9: Defendants may be required to disclose relevant evidence to support a claimant’s case.

- Article 10: Claimants must prove defectiveness, damage, and causality—though courts can lower the bar where scientific complexity of the device makes proving defectiveness challenging, but a causal link can be demonstrated.

- Article 19: Member States and the Commission must publish final judgments in product liability cases in accessible databases.

Conclusions and Analysis

- the revised Product Liability Directive significantly strengthens the liability environment for neurotechnology, raising expectations for manufacturers and increasing protection for consumers.

- Neurotech products often rely on AI algorithms, cloud-based processing, or mobile apps. The Directive explicitly recognises these as product components, meaning liability is not limited to physical devices.

- Many neurotech harms (e.g. worsening anxiety from neurofeedback, cognitive side effects of stimulation) fall outside physical injury. Recognising certified psychological harm is a major step for consumer protection.

- Proving causality in brain–computer interfaces or adaptive neurostimulation is notoriously difficult. By lowering the burden of proof in technically complex cases, the Directive increases the likelihood that injured users can obtain compensation.

- Liability is shared across the value chain, meaning neurotech companies cannot offload responsibility onto third-party software providers or distributors.

- While medical-grade devices are already covered by the Medical Devices Regulation, this framework ensures that non-medical consumer neurotech is also subject to strict liability rules if harm occurs.

Sources

General Product Safety Regulation (GPSR) - 2023

Introduction

The General Product Safety Regulation (GPSR) (2023) updates and strengthens the EU’s framework for ensuring the safety of non-food products. It addresses emerging challenges posed by new technologies, including risks from product modifications, cybersecurity vulnerabilities, and evolving functionalities. The regulation introduces mechanisms for monitoring and managing dangerous products, such as the Safety Gate Rapid Alert System, traceability requirements, and systemic obligations across the supply chain.

The GPSR covers all neurotechnology devices, including those intended for consumer or wellness purposes not covered by the Medical Devices Regulation.

The Commission will assess the GPSR’s effectiveness by 2029, ensuring governance evolves with technological advancements and business needs. It will adopt implementing acts that determine the specific safety requirements to be covered by European standards.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- Neurotechnologies with predictive or learning capabilities must undergo rigorous risk assessments, and substantial modifications may classify the modifier as the manufacturer with responsibility for safety compliance.

- Manufacturers must report incidents causing serious health effects, investigate complaints, and leverage traceability systems like the Safety Gate Rapid Alert System to address unsafe products.

- Compliance obligations extend to all parties in the supply chain, including importers and distributors, to ensure comprehensive safety management.

Selected Relevant Articles

- Recital (25): Highlights risks from new technologies, such as hacking and unintended consequences of modifications.

- Recital (35): Defines substantial product modifications and establishes proportional obligations for modifiers.

- Article 6: Lists aspects for assessing product safety, including cybersecurity, evolving functionalities, and user vulnerabilities.

- Article 7: The Commission shall adopt implementing acts determining the specific safety requirements to be covered by European standards.

- Article 9: Outlines manufacturers’ obligations to investigate complaints and accidents.

- Article 13: Deems substantial modifiers as manufacturers for safety compliance.

- Article 18: Introduces traceability requirements for high-risk products.

- Article 20: Mandates reporting of serious incidents involving product use.

- Article 25: Modernises the Safety Gate Rapid Alert System.

- Article 30(3a): Tasks the Consumer Safety Network with facilitating the exchange of safety methodologies and innovations.

- Article 47: Requires a regulatory evaluation by 2029 to assess its impact on safety and innovation.

Conclusions and Analysis

- The GPSR eddresses risks from evolving technologies, including cybersecurity threats, product modifications, and evolving functionalities.

- Its requirements for incident reporting, risk assessments, supply chain accountability, and traceability create a robust framework for identifying and mitigating potential hazards in neurotechnology devices.

- The regulation also facilitates innovation by ensuring that safety measures adapt to technological advancements, fostering consumer trust in new products.

- For neurotech manufacturers, compliance with GPSR provisions, particularly on risk management and post-market surveillance, will be critical for market access and regulatory adherence.

Sources

European Accessbility Act - 2019

Introduction

The European Accessibility Act (EAA) (2019) establishes a framework to eliminate barriers to the free movement of accessible products and services across the EU, particularly those important for persons with disabilities. By harmonising accessibility requirements, the Directive aims to ensure that accessible products and services are widely available in the internal market.

While it does not explicitly mention neurotechnology, its broad coverage of consumer products and digital services means that any neurotech product falling into these categories must be designed and marketed with accessibility in mind.

The EAA came into force in June 2025.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- The Directive addresses disparities in Member States' laws that discourage businesses, particularly SMEs and microenterprises, from entering external markets due to fragmented accessibility requirements. Neurotechnology products with interactive capabilities may need to align with these harmonised standards.

- Neurotechnologies that involve interactive computing capabilities (e.g. voice, video, or data processing) are likely subject to accessibility requirements ensuring they are usable by persons with disabilities.

- SMEs and startups developing neurotechnologies might benefit from the harmonised standards, enabling easier entry into multiple EU markets and greater competition and adoption of neurotechnologies across Member States. However, they must ensure compliance with accessibility requirements to avoid market access barriers.

Selected Relevant Articles

- Recital (1): Highlights the goal of eliminating barriers to the free movement of accessible products and services in the EU.

- Recital (5): Emphasises the need to address disparities in national accessibility laws to foster fair competition in the internal market.

- Article 2(1): Applies accessibility requirements to products, including consumer-grade computer hardware and operating systems. This could include brain-computer interfaces that rely on graphical user interfaces (GUIs) or other accessibility features.

- Article 3(39): Defines "consumer general purpose computer hardware systems," relevant to neurotechnologies integrated with desktops, smartphones, or tablets.

- Article 3(40): Establishes "interactive computing capability" as a criterion for accessibility, aligning with neurotechnologies requiring human-device interaction.

Conclusions and Analysis

- By improving accessibility, the Directive indirectly fosters innovation in neurotechnology, encouraging inclusive design and broader market opportunities.

Sources

Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (UCPD) - 2005

Introduction

The Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (UCPD) (2005) aims to harmonise laws across EU Member States to protect consumers from unfair business practices. This legally binding Directive applies to all business-to-consumer commercial practices, focusing on misleading, aggressive, or exploitative behaviors.

While not explicitly targeted at neurotechnology, its provisions are relevant to ensuring transparency and fairness in advertising, marketing, and sales of neurotechnology products.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- Neurotechnology companies are barred from engaging in misleading or aggressive tactics that distort consumers’ economic behavior.

- Special safeguards prevent exploitation of individuals with conditions affecting judgment, such as neurological disorders targeted by neurotech.

- Providers must disclose clear and truthful information on pricing, risks, and consumer rights, avoiding omissions that lead to uninformed decisions.

- Practices like harassment, coercion, or undue influence in selling neurotech devices are strictly prohibited to protect consumer autonomy.

Selected Relevant Articles

- Article 5: Prohibits unfair commercial practices, including those exploiting vulnerable consumers.

- Article 6: Defines misleading actions, such as false claims about product characteristics or results.

- Article 7: Prohibits misleading omissions, requiring sufficient and clear product information.

- Article 8: Defines aggressive commercial practices, including harassment or undue influence.

- Article 9: Prohibits the use of coercion, exploitation, or barriers to consumer rights.

Conclusions and Analysis

- The Directive plays a critical role in protecting consumers from unethical marketing and sales practices, ensuring neurotechnology companies act transparently and fairly.

- The emphasis on vulnerable consumers is particularly relevant for neurotech, as the target demographic of many of these products often includes individuals with cognitive or neurological impairments.

- Harmonised marketing standards across Member States simplify compliance for neurotech firms operating in multiple jurisdictions.

Sources

Health

European Health Data Space (EHDS) - 2025

Introduction

The European Health Data Space (EHDS) (2025) aims to create a unified framework for managing health data in the EU, empowering individuals to control their data while enabling its secure exchange for healthcare delivery (primary use) and research, innovation, and policymaking (secondary use).

Although it focuses on medical data, it may also apply to consumer neurotechnology depending on how neurodata is classified. It may also allow integration of wellness data from non-medical devices into Electronic Health Records (EHR).

The EHDS is a legally binding regulation recently published in the Official Journal, with implementation occurring in stages over the coming years.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- Neurotechnologies integrated into healthcare delivery will need to comply with interoperability and data-sharing requirements of the EHDS.

- Consumer neurotech companies may choose to participate in the EHDS framework. This would require revising data collection protocols and obtaining user consent for linking data to the EHR system.

- Industry stakeholders, including neurotech companies, could request access to anonymised health data for research and innovation purposes within a secure processing environment.

Selected Relevant Articles

- Article 2: Specifies what types of electronic data qualify as “health data” subject to EHDS rules. Explicitly includes medical device data, wearable sensor data, and other relevant digital health data.

- Article 7: Grants individuals the right to allow data transfer between healthcare providers, and to free access to health data.

- Article 8: Grants individuals the right to restrict access to their EHR with healthcare providers.

- Article 9: Grants individuals the right to know when their EHR has been accessed.

- Article 47: Specifies the labelling requirements necessary for wellness applications claiming interoperability with the EHR.

- Article 48: Allows wellness applications to claim interoperability with the EHR, and specifies that EHRs may not be automatically shared with the wellness application. Consent must be obtained and choice of which categories of data are shared must be given to the user.

- Article 54: Prohibits certain secondary uses of health data, such as for for restricting job offers, marketing purposes, or to create addiction.

Conclusions and Analysis

- By creating a unified, secure framework for neurodata, the EHDS has the potential to boost brain innovation and advance neurological medicine.

- Optional participation in the EHR system for wellness devices provides flexibility for manufacturers but requires consideration of interoperability and user consent.

- Aligning with the EHDS framework could offer benefits for wellness neurotech companies such as increased credibility, market access, and integration with the broader EU health data ecosystem.

Sources

Medical Devices Regulation (MDR) - 2017

Introduction

The EU Medical Devices Regulation (MDR) (2017), establishes a legally binding framework to ensure the safety, performance, and quality of medical devices across the EU.

It is particularly relevant for neurotechnology, including brain-computer interfaces and brain stimulation devices, as it covers systems interacting with the central nervous system and handling personal and clinical data. The MDR introduces strict requirements for pre-market assessment, risk management, clinical evaluations, and data handling, and includes specific provisions for neurotech without an intended medical purpose in Annex XVI.

The MDR is currently undergoing evaluation and potentially revision by the European Commission (as of April 2025).

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- Medical neurotechnologies must follow rigorous risk management protocols, addressing risks from data processing, device failure, and software updates.

- Developers must provide clinical evidence of safety and effectiveness, while ensuring data protection aligns with GDPR.

- Continuous monitoring and reporting of adverse events are mandatory to ensure long-term safety.

- Clear instructions and warnings are essential, especially for vulnerable populations relying on neurotechnologies.

- The MDR also applies to certain products without an intended medical purpose, including some neurotechnologies (Article 1(2), Annex XVI) such as brain-stimulating and implanted devices.

- Determing if a neurotech product qualifies as a medical device can be tricky, especially for borderline cases.

Selected Relevant Articles

- Recital (8): Establishes the responsibility of Member States to determine a product’s regulatory scope, with the Commission ensuring consistency in borderline cases through consultations with the MDCG and relevant EU agencies.

- Recital (59): Highlights the necessity of specific classification rules for invasive devices to address their toxicity and invasiveness.

- Article 1(2): Extends regulation to non-medical devices listed in Annex XVI, covering certain kinds of neurotech (mainly non-invasive brain stimulation).

- Article 9: Allows the Commission to adopt common specifications for safety, performance, and clinical evaluation in neurotech.

- Article 10: Outlines general obligations for manufacturers to ensure compliance with safety standards.

- Article 18: Implant card and information to be supplied to the patient with an implanted device.

- Article 61: Mandates robust clinical evaluation to demonstrate neurotech safety and efficacy.

- Article 89: Focuses on post-market monitoring, including analysis of incidents and corrective actions.

- Annex I: Details general safety and performance requirements, including programmable systems in neurotech.

- Annex XVI (2): Addresses products intended to be totally or partially introduced into the human body through surgically invasive means for purposes such as modifying anatomy or fixing body parts, excluding tattooing and piercings.

- Annex XVI (6): Specifically lists devices for brain stimulation that apply electrical currents, magnetic fields, or electromagnetic fields that penetrate the cranium to modify neuronal activity in the brain, requiring compliance with stringent safety rules.

Conclusions and Analysis

- The MDR ensures that medical neurotechnology devices meet the highest standards for safety, performance, and clinical evidence, particularly when interacting with the central nervous system.

- Its focus on risk management and data security addresses critical concerns for devices that process sensitive personal or clinical data.

- It emphasises ongoing vigilance, ensuring that safety risks are continuously monitored and mitigated throughout a device’s lifecycle.

- While strict, it leaves out many neurotechnology devices such as those used solely for monitoring brain function for wellness or entertainment purposes, or using stimulation technologies such as ultrasound, mechanical, thermal, or optical stimulation.

- Many neurotechnology devices therefore fall into a grey regulatory area as they are not required to be certified as medical devices. Yet, many of these devices offer health benefits such as reducing stress, and improving sleep and focus.

Sources and further reading

Opinion on the ethical aspects of ICT implants in the human body - 2005

Introduction

The European Group on Ethics (EGE) issued a non-binding opinion in 2005 addressing the ethical aspects of information and communication technologies (ICT) implants in the human body. This opinion highlights the potential risks of non-medical applications of such technologies, including threats to human dignity, privacy, and democratic values. Though not legally binding, the document provides an ethical framework for considering the societal implications of neurotechnologies and ICT implants.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- Non-medical ICT implants risk manipulating behaviour and compromising autonomy, raising concerns about exploitation and commodification.

- Neurotechnologies may enable invasive data collection, threatening privacy and potentially undermining democratic values through societal control and inequality.

- Emphasises stricter ethical scrutiny for non-medical applications due to their broader societal impact compared to therapeutic uses.

- Urges policymakers to implement safeguards and governance to mitigate misuse, particularly for non-medical technologies.

Conclusions and Analysis

- The opinion by EGE serves as a warning about the societal risks of neurotechnologies and ICT implants beyond medical contexts.

- It underscores the importance of balancing technological innovation with ethical considerations to prevent harm to human dignity, privacy, and democratic integrity.

- While non-binding, the document provides a valuable ethical framework for assessing the societal impacts of neurotechnologies and informing future governance approaches.

Sources

Cybersecurity

Cyber Resilience Act - 2024

Introduction

The Cyber Resilience Act (CRA) sets horizontal, technology-neutral essential cybersecurity requirements for all “products with digital elements” (hardware, software, and their remote data-processing components) placed on the EU market, with obligations covering design, development, production, and vulnerability handling across the product lifecycle. It harmonises rules EU-wide (free movement once compliant) and complements sector laws—notably excluding medical devices already covered by the MDR/IVDR—while tightening duties on manufacturers, importers, distributors, and open-source stewards.

The Cyber Resilience Act entered into force on 10 December 2024. The main obligations introduced by the Act will apply from 11 December 2027.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- Consumer wearables (e.g., EEG headbands or cognitive trackers) fall under the CRA; MDR/IVDR-regulated devices are excluded.

- Security-by-design: neurotech makers must build security in from the outset and maintain it over a defined support period.

- Supply-chain due diligence: developers must assess and govern risks from third-party and open-source components, including checking update history and known vulnerabilities.

- Risk-tiered oversight: certain “important” products (Annex III; incl. personal wearable health tech not under MDR) face stricter conformity assessment; “critical” products may be required to obtain EU cybersecurity certification at ≥ “substantial” level under the CSA.

- Actively exploited vulnerabilities and incidents are notified via an ENISA single reporting platform, enabling coordinated response.

- High-risk AI systems that meet CRA cybersecurity requirements can be deemed compliant with AI Act Art. 15 cybersecurity.

- Member States cannot add extra cybersecurity conditions for CRA-covered matters; SME support measures are foreseen.

Selected Relevant Articles

- Article 4: Free movement—no extra national cybersecurity requirements once CRA-compliant.

- Article 6: Essential requirements for products and manufacturer processes (Annex I, Parts I–II).

- Article 7 (+ Annex III): Important products (Classes I/II) are subject to stricter conformity assessment (referred to in Article 32(2) and (3)), including personal wearable health technology not under MDR.

- Article 8: Critical products may be mandated to obtain EU cybersecurity certification (CSA) at assurance level at least “substantial” through delegated acts.

- Article 11: Interaction with General Product Safety rules for risks not covered by the CRA.

- Article 12: High-risk AI deemed to meet AI Act cybersecurity requirements if CRA requirements are fulfilled/documented.

- Articles 13–17: Manufacturer obligations, vulnerability reporting, ENISA single reporting platform, and ENISA trend reports.

- Articles 19–22, 24: Obligations of importers, distributors, and “substantial modifiers” deemed manufacturers; cybersecurity policies for open-source stewards.

- Articles 31–32: Technical documentation and conformity assessment.

- Articles 52, 54–57: Market surveillance; measures for products presenting significant cybersecurity risks—even if otherwise compliant.

- Annex I: Sets out essential cybersecurity requirements.

- Annex III: Lists important products with digital elements (including personal wearable health tech not under MDR (Class I/19)).

Conclusions and Analysis

The CRA will be critical for consumer neurotech (especially wearables and apps), raising the baseline on lifecycle security, vulnerability handling, and supply-chain assurance while creating EU-wide coherence and clearer expectations for buyers and regulators. The exclusion of MDR/IVDR-certified products avoids double regulation of medical neurotech.

Sources

NIS2 Directive - 2022

Introduction

The NIS2 Directive (“measures for a high common level of cybersecurity across the Union”) updates the EU framework on cybersecurity for network and information systems. It expands upon the original NIS Directive (2016) by broadening the list of sectors and entities subject to cybersecurity risk management and incident reporting obligations.

While not applying to the majority of neurotech companies, NIS2 could cover devices or services deemed essential or important entities, particularly where they relate to healthcare or critical infrastructure.

As a Directive, NIS2 does not apply directly to companies; Member States must transpose it into national law, potentially introducing variations and stricter measures.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- NIS2 applies by default to medium-sized and large enterprises (≥ 50 employees, or annual turnover/balance sheet of ≥ €10 million). This means most small neurotech developers (e.g. hobbyist EEG headset sellers) will not fall under NIS2

- Small firms may still be covered: Member States may designate even micro or small companies as “essential” or “important” if they provide critical services.

- Neurotech products used in hospitals or as part of healthcare systems may be deemed “essential” under the directive.

- If a cyberattack compromises brain data or disrupts connected neurotech devices, the affected organisation must notify authorities promptly (within 24 hours).

- Businesses must ensure vendors and suppliers meet cybersecurity standards. Firms could face penalties if insecure third-party components create vulnerabilities.

Selected Relevant Articles

- Article 2(2): Allows Member States to designate smaller entities as “essential” or “important” if they provide critical services, even if they fall below the size threshold.

- Article 3(2): Defines essential and important entities, including medium-sized and large enterprises (≥ 50 employees or €10m turnover/balance sheet).

- Articles 7–13: Establish obligations for Member States (e.g. cybersecurity strategies, competent authorities, incident response teams).

- Article 21: Requires robust risk management measures to prevent and minimise cyber risks.

- Article 23: Specifies breach reporting procedures to national authorities within 24 hours.

Conclusions and Analysis

- Together with GDPR (for data privacy) and the Medical Devices Regulation (for device safety), NIS2 closes an important gap by focusing on digital resilience and protection against cyber threats to neurotech systems.

- However, most consumer neurotechnologies will remain outside its scope.

- Compliance will require coordination with healthcare providers, suppliers, and national authorities to ensure security across the entire value chain.

Sources

Cybersecurity Act - 2019

Introduction

The Cybersecurity Act gives ENISA a permanent mandate and creates an EU-wide cybersecurity certification framework for ICT products, services, and processes.

Although technology-neutral, it directly affects connected neurotechnology (devices, cloud services, BCIs, software) by promoting security-by-design, addressing third-party dependency risks, and enabling assurance levels for products whose failure could harm users’ privacy, dignity, or safety.

On 11 April 2025, the Commission launched a public consultation for input to evaluate and revise the Cybersecurity Act.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- Neurotech makers are expected to build and maintain security in devices and services from design through updates and end-of-life (security-by-design).

- Libraries, SDKs, and cloud modules used in neurotech stack create dependency risks that must be identified and governed.

- EU schemes can certify neurotech-relevant ICT components/services at basic, substantial, or high assurance levels, matched to risk.

- ENISA promotes cyber-hygiene and awareness for citizens and businesses—useful for consumer neurotech deployments.

- ENISA analyses emerging technologies and long-term threat trends—informing policy and best practice for neurotech.

- Once an EU scheme exists, overlapping national schemes are phased out to avoid fragmentation; national authorities supervise.

Selected Relevant Articles

- Article 1: Establishes ENISA’s objectives and the EU cybersecurity certification framework for ICT products/services/processes.

- Article 3: ENISA’s mandate—to support Member States/EU bodies and reduce market fragmentation.

- Article 8: ENISA’s role in standardisation and candidate certification schemes (prepare, recommend specs, evaluate).

- Article 9: ENISA to analyse emerging technologies, threats, incidents, and impacts.

- Article 10: Awareness-raising and guidance on good practices (incl. cyber-hygiene).

- Article 48: Commission may request ENISA to prepare or review EU certification schemes.

- Article 52: Assurance levels (“basic”, “substantial”, “high”) aligned to risk and evaluation depth.

- Article 57: National schemes cease for areas covered by an EU scheme; no new overlapping national schemes.

- Article 58: National cybersecurity certification authorities designated to supervise.

- Article 63: Right to lodge a complaint with certificate issuer or national authority.

Conclusions and Analysis

The Act provides a practical lever to raise the bar on neurotech cybersecurity: it embeds lifecycle security, focuses attention on supply-chain dependencies, and offers EU-level certification to signal trust (especially important for devices handling brain data or interacting with cognition). Its strengths are technology-neutrality and market harmonisation. A likely gap is that certification uptake depends on the availability and scope of relevant EU schemes, and coordination with sectoral rules (e.g., MDR) is essential to avoid duplicative assessments.

Practically, the Act’s basic–substantial–high assurance levels are only outlined in the Regulation; the concrete controls and testing depth are defined later in each EU certification scheme. For neurotech, this means the bar to clear depends on the scheme covering the device or cloud stack—low-risk consumer tools may be considered basic/substantial, whereas clinical-grade or safety-critical neurotech will likely be pushed toward high.

Sources

Data governance

Guidelines on prohibited artificial intelligence (AI) practices - 2025

Introduction

The European Commission’s AI Act Guidelines (published in February 2025) provide non-binding but influential interpretation of how the AI Act (2024) should be applied. They help clarify ambiguous provisions, especially concerning prohibited AI practices under Article 5.

For neurotechnology, the Guidelines are highly significant. They explicitly discuss subliminal manipulation, purposefully manipulative and deceptive techniques, and emotion recognition systems—all of which may be relevant to brain–computer interfaces, neuromarketing, mental health devices, or consumer neurotech applications. This is also the first official EU-level document that specifically references practices such as dream-hacking and brain spyware — largely considered science-fiction until only very recently.

While the Guidelines do not create new legal obligations — with authoritative interpretations reserved for the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) –- they shape regulatory expectations and may influence future enforcement.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- Subliminal techniques: AI combined with neurotechnology (e.g. EEG-based games or neuroadaptive interfaces) could covertly influence user behaviour or extract highly sensitive information without awareness. Such uses are prohibited if they cause significant harm, but machine-brain interfaces in general are not — when designed in a safe and secure manner that is respectful of privacy and individual autonomy.

- Manipulative techniques: Systems exploiting psychological vulnerabilities (e.g. attention, cognitive bias, mental health conditions) are prohibited, even if the provider did not intend harm. Neurotech tools designed to nudge or alter user states may fall under scrutiny.

- Deceptive techniques: AI systems presenting false or misleading information to shape decisions undermine autonomy and are prohibited. This is relevant to neurotech applications that frame feedback in misleading ways (e.g. overstating efficacy of brain training).

- Emotion recognition: Emotion inference from biometric data—including EEG, ECG, gait, facial expressions, keystrokes, or other neurophysiological signals—is within scope. This covers many neurotech consumer and workplace products marketed for mood or attention tracking.

- Biometric basis matters: Emotion analysis from brain signals (e.g. EEG headbands) falls squarely under prohibition, whereas emotion inference from non-biometric data (e.g. text sentiment analysis) does not.

Selected Relevant Sections

- Section 3.2.1 (Subliminal techniques): Defined as operating below conscious awareness, bypassing rational defences. Neurotechnologies using covert brain stimuli or AI-driven training without user awareness may qualify as prohibited. Machine-brain interface applications in general, when designed in a safe and secure manner and respectful of privacy and individual autonomy, are not prohibited.

- Section 3.2.1 (Manipulative techniques): Includes AI systems that exploit biases or vulnerabilities, even unintentionally. Relevant where neurotech “nudges” mental states or uses reinforcement learning that evolves manipulative behaviours.

- Section 3.2.1 (Deceptive techniques): Involves presenting false or misleading information that undermines decision-making. Relevant for neurofeedback or consumer neurotech overstating outcomes.

- Section 7 (Emotion recognition, Article 5(1)(f)): Covers AI systems inferring emotions from biometric data, including EEG and other physiological signals. Emotions should be interpreted broadly, but do not include physical states, such as pain or fatigue. Explicitly excludes text-based sentiment analysis.

Conclusions and Analysis

- The AI Act Guidelines significantly narrow the scope for potentially manipulative or emotion-inferencing neurotechnologies, especially those using biometric or brain-based data.

- The Guidelines confirm EU regulators’ concerns about covert influence and biometric monitoring. Devices marketed for entertainment, wellbeing, or education could be scrutinised if they include subliminal nudges, manipulative reinforcement loops, or covert biometric-based emotion tracking.

- Emotion recognition in advertising, recruitment, or employee monitoring falls within prohibited practices if based on biometric data like EEG or gait.

- On the medical vs non-medical divide, while some neurotech in healthcare may seek exemptions for legitimate medical use, the Guidelines signal strict scrutiny on consumer and commercial contexts.

- Even though non-binding, these guidelines are likely to shape how national authorities interpret “harmful subliminal” or “emotion recognition.”

Sources

AI Act - 2024

Introduction

The EU AI Act (2024), establishes a legally binding framework for the development, deployment, and use of artificial intelligence within the EU. The Act introduces risk-based classification, transparency requirements, and prohibitions on harmful AI practices. It aims to ensure AI systems are trustworthy, safe, and aligned with fundamental rights obligations.

Neurotechnologies often employ AI to interpret brain signals. Under the AI Act, some applications are entirely prohibited (e.g. subliminal messaging and manipulation, exploitative uses), while many others will be treated as high-risk AI systems—including medical devices using AI for diagnostics, biometric categorisation, or emotion recognition. These systems must meet strict requirements for conformity assessment, transparency, risk management, and human oversight.

By contrast, certain consumer neurotechnologies may fall outside the high-risk category—or even outside scope—if they are used solely for scientific research, do not rely on AI, or apply AI in low-impact ways (e.g. simple wellness or entertainment features). However, once a consumer device engages in biometric categorisation, emotion recognition, or other sensitive applications, it will fall under the high-risk classification or face outright prohibition.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- Prohibitions: AI-enabled neurotech must not use subliminal or manipulative techniques that distort behaviour, exploit vulnerabilities, or engage in prohibited biometric categorisation (e.g. inferring political beliefs or sexual orientation). Emotion recognition is banned in workplaces and education, unless for health or safety.

- Research exemption: AI used exclusively for scientific research is exempt, providing more freedom for early-stage neurotech research and innovation.

- Transparency: Deployers of biometric categorisation or emotion recognition systems (including those based on EEG or other neural data) must inform affected individuals and comply with GDPR.

- Systemic risks: General-purpose AI models that could be applied to neurotech (e.g. brain–AI language decoders) may be designated as posing systemic risk, subject to heightened scrutiny.

- Stricter on biometric data: The AI Act defines biometric data (Article 3(34)) in a narrower way than GDPR, thus neural data will likely be classified as biometric data. Contrary to the GDPR, the AI Act does not require that biometric data be able to identify a person, rather simply data resulting from “physical, physiological or behavioural characteristics of a natural person”.

Selected Relevant Articles

- Recital (29): Highlights the prohibition of manipulative AI practices, including subliminal techniques, to prevent significant harm or distortion of behaviour.

- Article 2(6): Exempts AI models developed and deployed specifically for scientific research.

- Article 3(24): Biometric data is defined as "personal data resulting from specific technical processing relating to the physical, physiological or behavioural characteristics of a natural person, such as facial images or dactyloscopic data;"

- Article 5: Lists prohibited AI practices, several of which are highly relevant to neurotechnology:

- subliminal or manipulative techniques if they distort human behaviour in a way that impairs informed decision-making

- exploitative uses targeting vulnerable individuals

- profiling and evaluation of personality characteristics, either for social scoring or to predict criminal activity

- emotion recognition in the workplace or in education, unless for medical or safety reasons

- biometric categorisation to infer race, political opinions, religious or philosophical belief, sexual orientation.

- real-time remote biometric identification systems in public spaces

Exceptions to these prohibitions include for reasons of health and public safety.

- Article 6: Defines high-risk applications of AI as those acting as a safety component, for example in a medical device, as well as all those listed in Annex III elaborates on these. Exempt are systems that do not pose a significant risk of harm to the health, safety or fundamental rights of natural persons.

- Article 26: Requires deployers of biometric categorisation and emotion recognition systems to inform affected individuals and process data in accordance with GDPR and other regulations.

- Article 50(3): Sets transparency obligations for deployers of biometric categorisation and emotion recognition systems.

- Annex III: Categorises the following AI systems as high risk:

- biometrics (categorisation and emotion recognition)

- education

- employment

- migration and border control

- administration of justice and democratic processes

Such high-risk applications face additional requirements, such as transparency, human oversight, and a sufficient level of accuracy.

- Annex XIII: Establishes criteria for determining systemic risks in general-purpose AI models, which could include neurotechnology applications.

Conclusions and Analysis

- The AI Act represents a significant milestone AI governance, particularly for high-risk applications which include many neurotechnology applications.

- It ensures the high-risk systems undergo rigorous oversight while prohibiting harmful or exploitative practices, and prevents fragmentation of the EU internal market by standardising obligations across Member States.

- As neurotechnologies are not specifically mentioned, it may be complex to interpret certain provisions, for instance where to draw the line between assessing mental state and emotion recognition, or what constitutes significant harm to health and fundamental rights.

- Neural data - biometric - definition vs recital (see Onur's comment)

Sources and further reading

- EU AI Act (Regulation (EU) 2024/1689)

- Bublitz, C., Molnár-Gábor, F., Soekadar, S., Implications of the novel EU AI Act for neurotechnologies, Neuron, Sep 2024.

- Istace, T. Neurodata: Navigating GDPR and AI Act Compliance in the Context of Neurotechnology. Geneva Academy, Jan 2025.

Data Act - 2023

Introduction

The Data Act (2023) is a horizontal regulation aimed at unlocking access to and use of both personal and non-personal data across the EU. It establishes rules for data access, portability, and sharing, particularly from connected devices and services. While not specific to neurotechnology, the regulation is highly relevant as many neurotech products—such as wearable EEGs, BCIs, and digital therapeutics—generate data that may fall under its scope.

The Data Act is part of the EU's broader strategy to build a single market for data, ensuring innovation, fairness, and user empowerment in the data economy.

It entered into force on 11 January 2024.

Key Takeaways for Neurotechnology

- Applies to connected neurotech devices that generate data during use—users may have the right to access or share this data with third parties (e.g. clinicians, researchers, or app developers).

- Encourages interoperability and data portability, which could facilitate switching between neurotech platforms and reduce vendor lock-in.

- Neurotech companies must design products with data access in mind from the outset (“data by design”), impacting hardware and software development.

- May shape future business models, requiring firms to rethink how they monetise data collected from brain–computer interfaces or other devices.

- Safeguards against unlawful third-party or extra-EU government access to non-personal data, adding another layer of protection for sensitive neurodata.

- Users and companies can access certified dispute settlement mechanisms and complaint procedures if their data access rights are infringed.

Selected Relevant Articles