Your brain is not just a sponge that can soak up and hold unlimited amounts of information. You are better able to recall things if:

- You have “learned them by heart”, through endless repetition

- They are connected to other ideas

- You have learned them by practicing

- You understand the theory behind them well enough to see patterns and make predictions

There is a limited number of ideas that you can learn by heart. Typical examples are the letters of the alphabet, months of the year, family birthdays, your bank card PIN, or multiplication tables. You do not need to understand the theory behind them – you just know them as facts.

You are more likely to remember information for the other reasons listed above. For example, you may have learned to swim through physical trial and error. It is impossible to learn how to swim by reading books. Even if someone could find the words to explain how swimming works, and you memorized all of it, you would be unable to translate it into effective action without practicing it.

Learning is a process and requires practice, not simply exposure to information. You are best at remembering the things that you do.

You might assume that only physical activities can be practiced, but there are many ways to “practice” abstract ideas to help you to internalize them. You can write about them, answer questions about them, draw diagrams of them, explain them to others or even explain them to yourself. Every time you practice, recall gets easier.

When you make notes about something in your own words or manipulate ideas and information in a diagram, you practice explaining it to yourself. While you are studying, you should always ask yourself how you would explain it to someone else. Being aware of the steps in someone else’s learning process leads to awareness of your own.

Working with a software tool like Mindomo will help you to organize better, deal with more information, and integrate it more effectively than passive reading and reliance on memory.

Step 1: Know what you are aiming at

The first thing to do is to be clear about what you want to do with your new-found learning, and why. All your studies will be driven by this.

If you are a professional learning a new skill for work, you may already be motivated because new responsibilities and opportunities may open for you.

If you are studying in school, the goal might be clear (to pass an exam), but the purpose might be vague. The subject may be uninteresting, or you may be unable to imagine a situation where this knowledge will be useful to you. But as we hinted earlier, learning how to learn is a more useful life skill than any specific knowledge of historical dates or dinosaurs. You could decide that in some subjects your purpose is to be better at learning and helping others to learn, even if this subject is not very inspiring for you. You could search for ideas that relate to interesting subjects. Having specific interests is good but being able to make lateral connections to other subjects is better, as this will deepen your knowledge of the things that you are interested in.

Whatever your goals and purposes are, write them down somewhere so you can see them regularly, and refer to them to help with focus and decisions.

Step 2: Stay organized

Being organized is critical. To use your time effectively you need to be able to pick up your studies and make progress without having to search for things, work out where you got up to last time and work out what you need to do next. These are common forms of procrastination, and you can easily find that the time allocated to study is eaten up by getting ready to study.

Making plans can be helpful but making ambitious plans then routinely failing to finish them can become an unproductive habit. Just having all your stuff organized is a good start, even if you are not ready to work on detailed schedules. You should at least write down important dates such as exam dates where you can see them regularly.

Step 3: Scope it out

Next, you need to know the boundaries of your studies, so that you can make sure you cover everything that will be required. As Jordan Peterson says, it is better to go and find the dragon in his lair than wait for him to come and find you.

If you are studying in school or for an exam, the syllabus may have been provided already. If not, then ask for it. If you are taking a professional training course, the contents or syllabus should be published.

Write out the syllabus in your own words, and if possible, ask your lecturer about the wider objectives for each part of the syllabus. How this will help you? What does it depend on? What is it preparation for?

Including an overview of the syllabus in your Mindomo map will help to reduce overwhelm. It also enables you to keep track of context and progress throughout the course.

Step 4: Build resources

There will be a lot of resources thrown at you during your studies – books, reading lists, essays, manuals, lectures, videos, and test papers to name a few. You should have a system for organizing it all and finding things when you need them. Any system will do, provided you have a system.

But of all the resources at your disposal, time is the most important one. You can’t borrow time from someone else, or find some more if you run out. Some people are good at doing everything at the last minute, but even if you are good at this, it is a high-risk approach. You might plan to be a revision hero the week before an exam, but an unexpected incident could derail that and leave you without any options. You might discover that you had somehow missed a whole section of the syllabus, or something might happen that is genuinely a higher priority than your revision. A less intense effort spread over a longer period will always win out against the last-minute risk-takers.

Other resources to add to your list are:

- People – think about who could help you, who has experience in this area, for example, who has taken this exam before

- Your own research

- Communities of interest, e.g., online forums of potentially knowledgeable people. Be aware that everyone thinks they are an expert and may be simply confusing opinion with experience.

- Opportunities to apply or share your knowledge. Testing your ideas and knowledge is the ultimate way to learn.

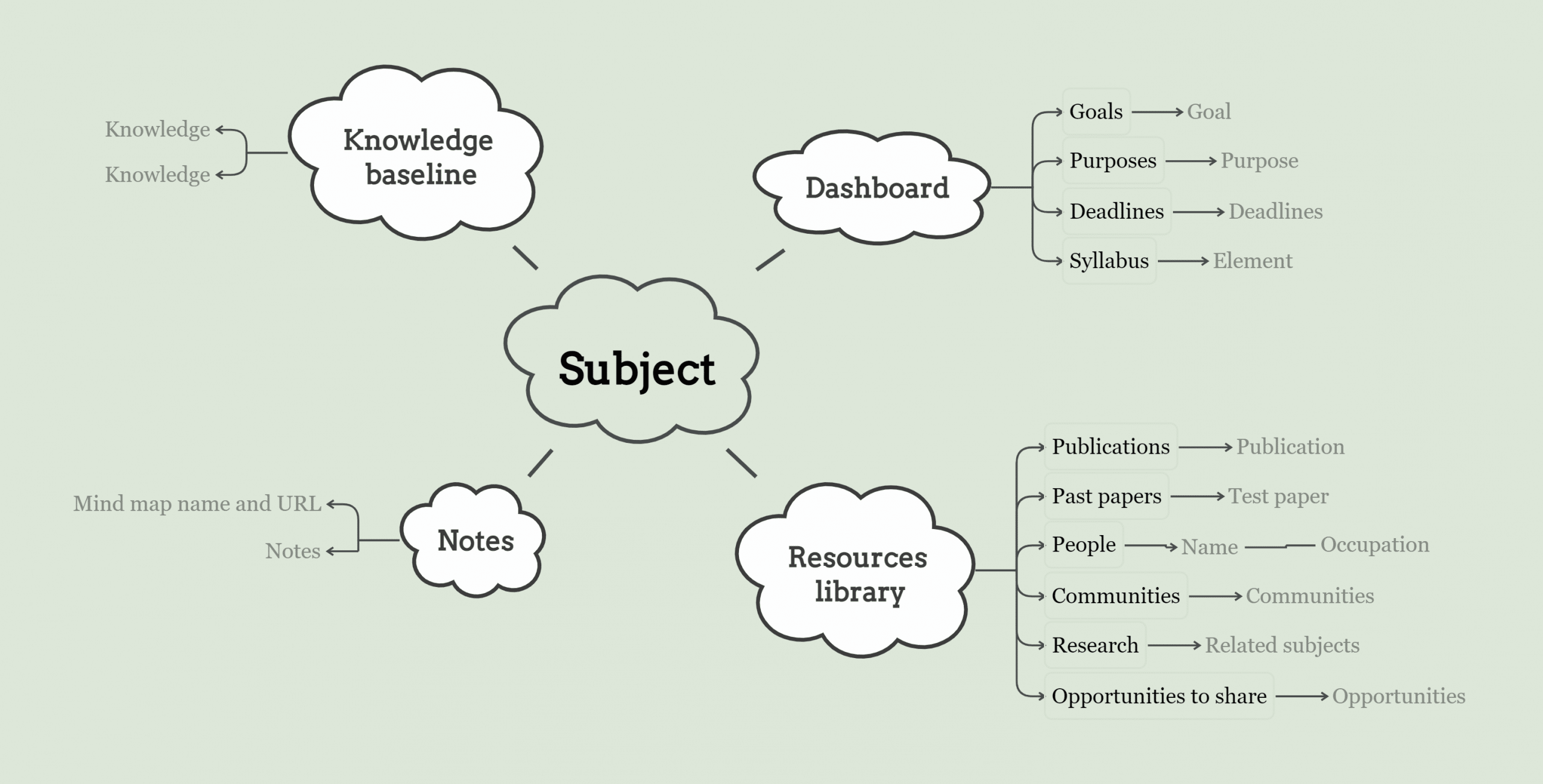

Gathering and updating your resources list is something that you will do all the way through studying. Having a system will help you to find things again when you need them. If you are using Mindomo to support your learning process, make a map with links to resources. The template map “Studying with Mindomo” has a placeholder for this.

Step 5: Know what you know

Everything you know is connected to other things that you know. You might know a few totally random and useless facts, but even these are related to each other by being on a list of random, useless facts.

Effective learning always builds on what you already know.

When your lecturer suddenly presents a concept, formula, or theory that makes no sense to you, you will be searching for some way to relate it to existing knowledge. If you ask your lecturer to explain it again, they will often simply repeat themselves, make circular references, or try to add more detail on top of something that you don’t understand in the first place. What you need is for them to explain how it is connected to things that you do understand. It’s important to ask them to do this, rather than say “OK, thanks” and wait for some other piece of information to eventually unlock it.

It is difficult for people to imagine what it is like to not know something, and difficult to verbalize the related but unspoken knowledge that makes something understandable. A competent swimmer might think a book about learning to swim contains everything you need to know, forgetting that they have a lifetime of experience behind their own ability. This unspoken knowledge is a form of “tacit” knowledge and is an essential part of integrating knowledge.

Try to make a rough list of what you already know about the subject that might be relevant to your new studies. You probably know more than you think. Making mind maps is a wonderful way to discover this and helps you to make connections between new things and things you know.

Step 6: Collect

Being able to take effective notes from books, lectures, videos or conversations is the foundation for effective study. Note-taking is a big subject. A few tips:

- Other people’s lecture notes are no use to you. They only work as a reminder of a lecture if you were there

- You must write things in your own words, not copy them verbatim. Copying requires no comprehension or even thinking. By contrast, phrasing something in your own words requires you to think about it

- At a meeting or class, writing notes works better than typing on a computer. Writing is faster, you can draw sketches, and a notebook doesn’t create a physical barrier or distraction

- Highlighting in books or making notes in the margin doesn’t work. Your notes need to be where you can connect and review them in your own frame of reference, not scattered across multiple places

- Always record the source of something so you can find it again

- Ideally, your notes need to be turned into a format where you can easily connect them to other ideas

Reading

Much is written about speed reading, including an earlier post in this blog [1]. Being able to read quickly may save time, but only if you don’t sacrifice understanding for speed. A process that works well for some people is:

- Always read with a pen and paper to hand

- Begin by skimming the main sections or chapters, to get an idea of the overall structure. Look at the diagrams and pictures as these will be important markers in the text

- Look for introductions that explain who it is written for and whether it is relevant to your needs

- Work out which parts are telling the story, and which parts are appendices or reference sections that you could skip without losing the thread. You can review them later when you are better able to understand them

- You can then return to the beginning and read, making notes as you go

- Read until you encounter something that you don’t understand. If necessary, go back and see if there was some earlier helpful point that you missed. If you cannot resolve it, write it down as a question and carry on

- When you make notes of important points, write down the book title and page number so that you can find them again

- If you are making notes in a Mindomo map, pause every now and then to tidy up and restructure the map as your understanding develops

If your list of open questions just gets longer and longer, it will become more difficult to continue reading while mentally tracking a lot of loose ends. You might need to get some help or research other areas to make sure you understand the key points, otherwise, you will not get the full value from the book. You should not feel too bad about needing to do this; sometimes authors are unclear about who their audience is or don’t manage to put their ideas in a sequence that helps the reader to build up knowledge in steps.

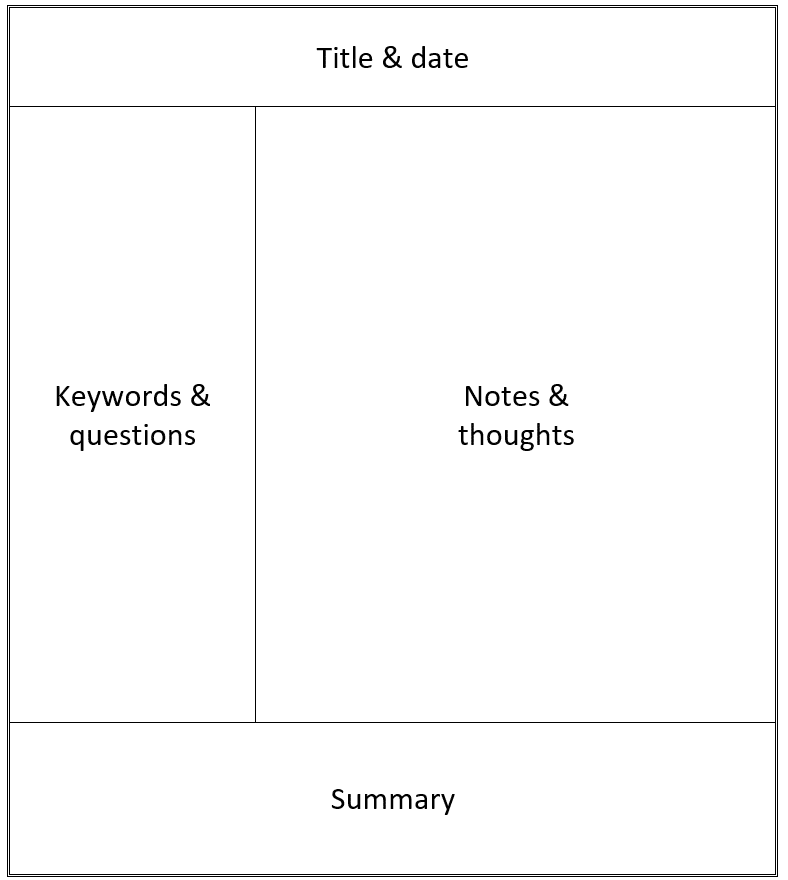

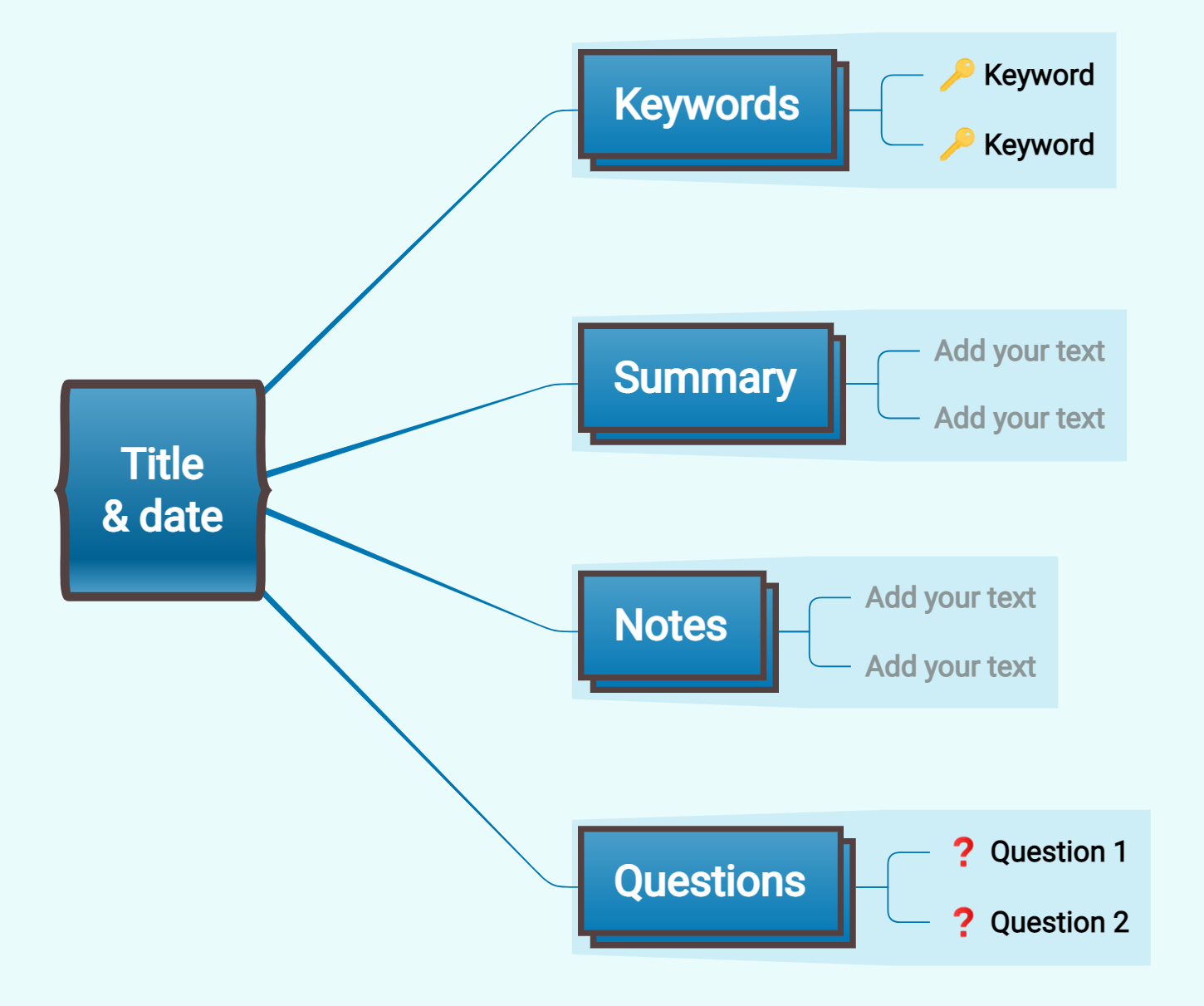

Cornell Notes

Cornell Notes [2] are a way of taking structured notes that are much easier to review afterward. You can do this on paper or translate the ideas to Mindomo later. The parts of a Cornell note are:

- The title and date

- Notes and thoughts about the subject

- Keywords to which these notes relate

- Questions that you have about the subject

- A summary of the main points

Cornell Notes can be quickly sketched out on paper:

Figure 3: Cornell Notes layout

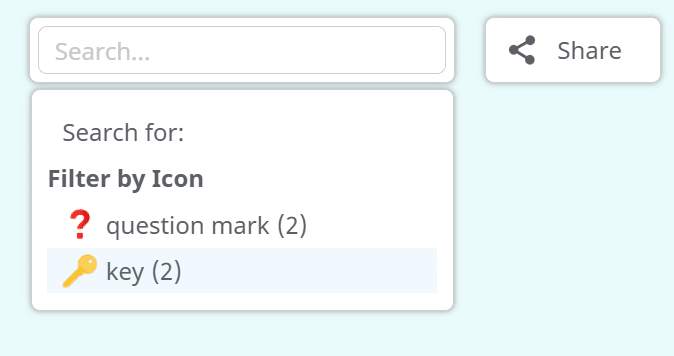

If you are using Mindomo to store and organize permanent notes, there are advantages to organizing similar information on a map:

Figure 4: Cornell Notes structure in a Mind Map

Using the “Key” and “Question” icons on keywords and questions in your map makes it easy to filter the map. For example, you can quickly view the keywords in your map by clicking on the Search button and selecting the key icon. This will show only the keyword topics on your map.

Figure 5: finding keywords in a map

This will work regardless of where the keyword topics are on your map.

Zettelkasten method

If you want to get serious about writing notes, have a look at the Zettelkasten Method [3] and find a way to implement it that works for you. The basic ideas behind the Zettelkasten Method are:

- Make fleeting notes (quick and rough notes) in all situations.

- Re-write your fleeting notes as permanent notes soon after the event, in your own words.

- A note should be “atomic”, i.e. a single idea about one subject. Avoid mixing ideas or making them complicated.

- Use keywords to help you find things later.

- Always record the source.

- Connect notes and ideas to each other, so that you build a network of connected concepts. This directly builds on the idea that new knowledge is always linked to existing knowledge.

Step 7: Build on what you know

Everything up to now has been about getting organized and gathering information. The heart of studying is being able to link new ideas to existing ones because this will help with understanding and recall.

This is where visualization plays an important part. A well-constructed diagram is a shortcut to the mental model that you build when you read some text, interpret it, and then try to picture it internally. Words are a narrow pipe through which we try to transfer complex ideas, hoping that the reader can reconstruct the same concepts at the other end.

The diagrams that work the best for studying are the ones you have drawn yourself. Writing has been around for thousands of years, and printing has been in our technical toolkit for about five hundred years. The ability to rapidly draw, manipulate and revise diagrams at scale is less than 25 years old (at the time of writing), and the value of doing so is still being understood.

Of course, we can make notes and draw diagrams on paper. While technology depersonalizes this a little, the advantages that it brings are scalability, searching, and modification. You can draw electronic diagrams that are many times bigger than could be fitted onto a sheet of paper, and can then rapidly search them for keywords. You can also make large changes in a second or two that would take an hour on paper. This ability to manipulate greatly enhances understanding and recall because you are making and remaking connections.

There are many well-known types of diagrams that are useful for structuring ideas and information, such as grids, pie charts, line charts, timelines, and so on. If you are using Mindomo to support your studies, the two main types of diagrams that will help you are Mind Maps and Concept Maps.

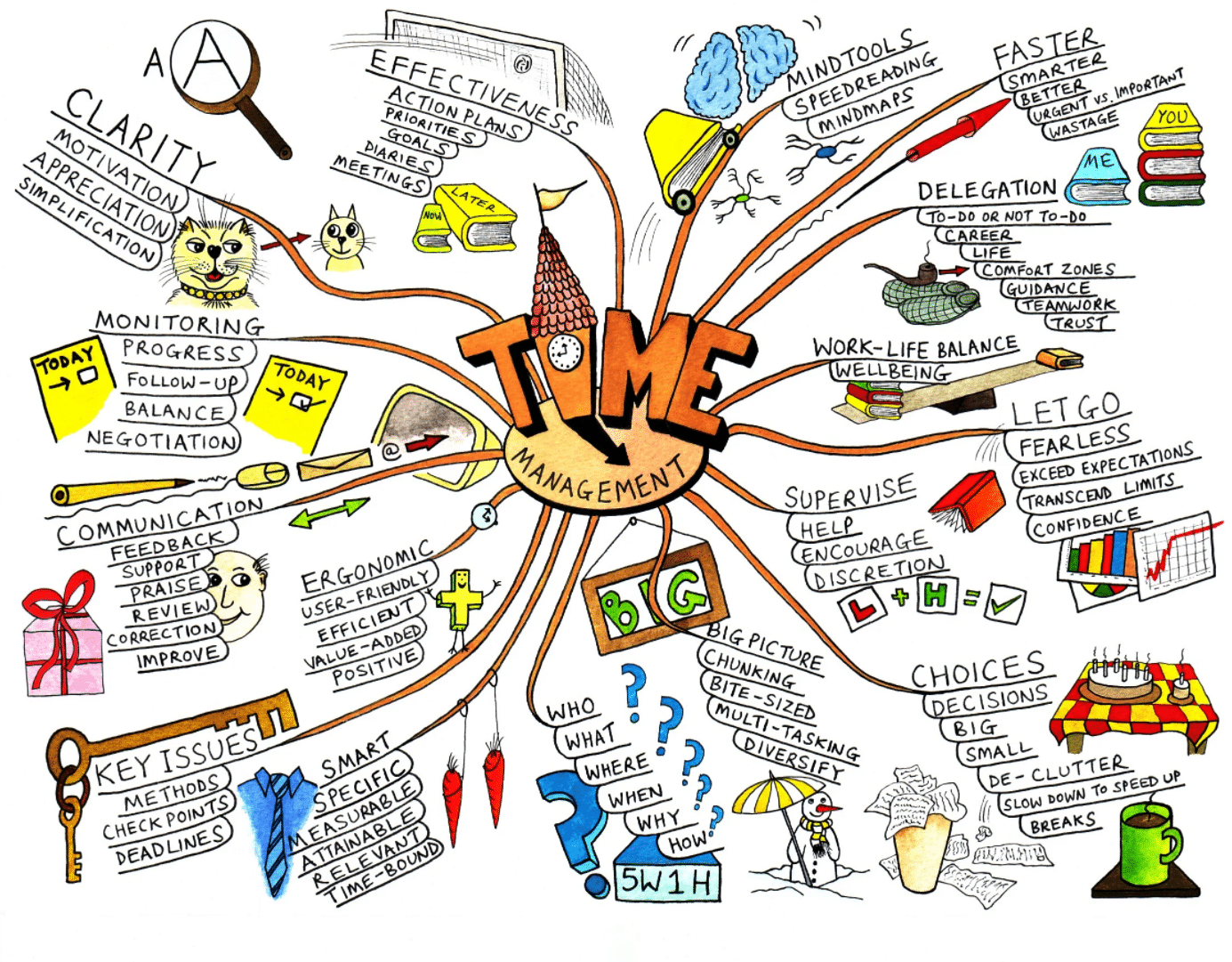

Mind maps

There are many articles on the Mindomo website [5] and elsewhere explaining what is a Mind Map and how to draw it. The critical point about Mind Map Diagrams is that the benefit comes from building the map yourself. Like other people’s rough notes from a lecture, mind maps created by others may be of lower value to you.

Figure 6: A hand-drawn Mind Map [4]

For the purposes of learning and revision, you are aiming to capture information in a form that reinforces connections and is easier to recall than linear text.

Although mind mapping software can do much more, it is still worth knowing the basic principles of Mind Maps as these are designed to help you to learn and recall:

- Keep topic names short

- Use plenty of colors and images

- Write more detailed explanations of ideas in the topic notes

- It helps if maps are logical, but this is not essential. What matters is that they remind you of connections

- Review your maps often (or better, copy them out by hand) to keep them fresh in your mind

If you are drawing Mind Maps on paper, you will find that you need to make several revisions when you run out of space in an area that turns out to be more complicated than it first appeared. If you are using Mindomo, this will not be an issue as the layout adapts when you add new topics.

- Begin by collecting ideas and information in one place

- Drag and drop them to group and organize, with big ideas nearer the center of the map

- Look for patterns and gaps

- Look for definitions of specific terms and highlight them in your map

- Draw relationships across your map to connect related ideas

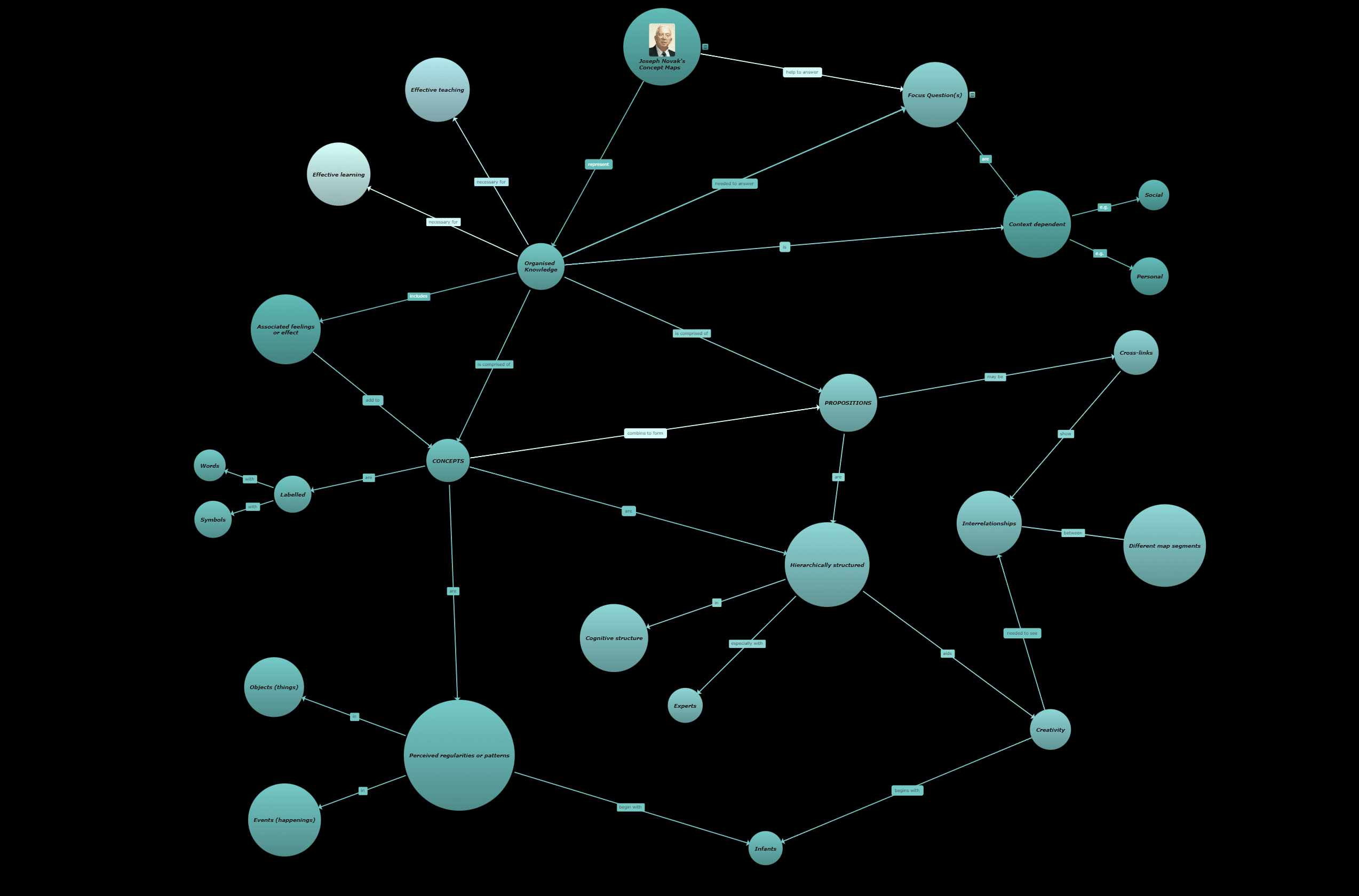

Concept Maps

Concept Maps are different from Mind Maps. They are designed to answer a “Focus Question”. The Concept Map below aims to answer the questions “What is a Concept Map, and how do they work?” [6, 7, 8, 9]

Figure 7: A Concept Map about Concept Maps

When you link two ideas in a Mind Map, you just connect them directly, either as parent and child topics or with a plain relationship.

Figure 8: Dinosaurs and Velociraptors are connected in a Mind Map

When you link two ideas or concepts in a Concept Map, the connection has a specific direction and a short description.

Figure 9: “Velociraptors are a genus of Dinosaurs”

This is a much more powerful way to understand relationships. We can read phrases (propositions) from Concept Maps by following the arrows from one concept to another. Phrases are often easier to remember than keywords.

Concept Maps are more difficult to draw on paper because you frequently need to reposition the concepts to add more. But it is always worth capturing some basic ideas on paper first. Mindomo can draw Concept Maps using floating topics connected by relationships and also helps you to layout your diagram.

Use Concept Maps when:

- You need a deeper understanding of how things are related to each other

- The subject is not a nice simple tree, but each concept relates to multiple others

- There are a limited number of concepts or ideas to link together. Concept Maps become difficult to read and use when you have more than 20 or 30 ideas in them.

Concept Maps take a little longer to draw but are more transferable than Mind Maps. It is easier to understand someone else’s Concept Map because everything is explained. But like Mind Maps, the real value comes from creating your own, using your own words.

Step 8: Practise

The final step in our studying process is to keep practicing what we are learning.

“Revision” is often pushed to the end of the study, with the goal of remembering as much information as you can for only a week or two until the exams are over. Cramming before an exam can only really help with memorizing facts, not building knowledge. You are starting from a weaker position than if you had steadily built up your knowledge over time. Two weeks before an exam is the wrong time to start reading your lecture notes again and discovering that you thought you understood it at the time but didn’t really.

At the start of this article, we mentioned that learning takes place when you build on what you already know. This is a gradual process. It takes time to absorb an idea, relate it to other things, and use it effectively in other contexts. Again, this is not something that you can do the night before an exam. It is more sustainable and survivable to slowly fill the “what I know” pool than to try to flood it at the last moment.

You can continually strengthen your knowledge by:

- Regularly converting fleeting notes into more permanent notes

- Regularly reviewing, updating, and redrawing your maps

- Writing about the subject

- Adding new resources to your resource library

- Understanding what has been left out of the syllabus

- Reading outside the syllabus and extending your notes

- Taking every opportunity that you can to explain things to other people

- Looking for connections or similar patterns between subjects that seem to be unrelated

All these things are more effective than simply reading and trying to memorize.

Conclusions

If you have read this far, well done!

The key points we have discussed are:

- Always look for ways to improve your learning skills

- Learning must build on what you already know

- Write things in your own words, not someone else’s

- You learn by doing; writing about things, connecting ideas, and explaining them will help you to learn

- Drawing and improving diagrams is a very effective way to learn

Where next? You could start by making your own Mind Map of this article, to summarise it in your own words. There is also a template, “Studying with Mindomo”, which helps you to create a dashboard map for each subject.

Good luck with your studies!

References

[1] Mindomo Blog, 26th May 2021 10 Mental Hacks for Faster Reading and Better Retention (mindomo.com)

[2] Wikipedia article on Cornell Notes

[3] Wikipedia article on the Zettelkasten Method

[4] Jean-Louis Zimmerman, Time Management Mind Map, Flickr (Creative Commons license)

[5] Mindomo article: What is a Mind Map?

[6] From a presentation by Dr. Joseph Novak

[7] IHMC web site

[8] Mindomo’s article: What is a Concept Map?

[9] Mindomo template: “Joseph Novak’s Concept Maps”

[10] Mindomo template: “Studying with Mindomo”

Keep it smart, simple, and creative!

Author: Nick Duffil